The role of close relatives in the allocation of long-term nursing home beds

Close relatives help patients to live at home longer and are an important resource for the welfare state. But they can also contribute to an unfair allocation of nursing home beds by advocating for their own family members.

Background: The rising number of elderly people is putting increasing pressure on municipal health and care services. This means, among other things, that getting a bed in a nursing home can be more difficult. To ensure a fair allocation of beds, it is crucial to obtain knowledge about the factors that influence how priorities are set. We must therefore also understand the role that close relatives play in the allocation process.

Objective: The article aims to investigate the role of close relatives in the allocation of long-term nursing home beds.

Method: The study employs a qualitative method with an exploratory approach. We included four municipalities and conducted 16 interviews with case officers in the allocation offices and with registered nurses and doctors on short-term wards. We also observed 13 meetings between case officers and healthcare staff on the short-term wards, and we performed a thematic content analysis of the interviews and field notes.

Results: The study participants felt that close relatives play a crucial role in the process of allocating municipal health and care services. Close relatives can be an important care resource and thus also act as a ‘buffer’ in the system. At the same time, they are often the driving force behind the allocation of long-term nursing home beds, which can jeopardise our ideals of fairness and equal treatment.

Conclusion: It is important to have transparent allocation processes and additional focus on patients who do not have resourceful relatives. Close relatives who act as buffers in the health services require attention and respite. Clearer guidelines are needed to define the responsibilities of close relatives versus those of the public authorities.

Norwegian law stipulates that municipalities must ensure that all residents are offered health and care services (1). The municipal health and care services must be adapted to various patient groups, which often have highly diverse needs (2).

After implementation of the Coordination Reform, the municipal health services assumed responsibility for more tasks, but did not receive additional resources (3–5). The figures for 2013 show that the need for 24-hour care services will increase by 15 000 up to 2030 and by 45 000 up to 2050 (6).

This need will put more pressure on municipal finances, as 24-hour care requires more resources, both in terms of money and competence. In addition, an important political guideline states that patients should live at home as long as possible (7).

Objective of the article

Patients living at home with complicated conditions and complex needs often place a greater burden on their close relatives. It is estimated that close relatives currently provide about 50 per cent of the health and care services needed. Policy guidelines point out that there will be an even greater need for assistance from close relatives in the future (6).

The article aims to investigate the role of close relatives in the allocation of long-term nursing home beds.

Previous research on the significance of close relatives

Fjelltun et al. have shown that close relatives go to great lengths to provide care for patients living at home (8). Studies also show that having close relatives can reduce the need for long-term nursing home beds (9).

Close relatives provide care largely in the form of invisible labour and meet the need for health and care services (10, 11). They also assist a great deal with medical treatment (12, 13) and are often described as pillars of support or invisible cornerstones (11, 13, 14).

While close relatives provide care, research also shows that patients who have close relatives are given priority when health and care services are allocated (15). Studies show that close relatives feel it is both a duty and a struggle to care for patients in the home (16, 17).

Many feel pressured by expectations that they must help with the treatment and care of their family members (13). When they can no longer manage it, they may feel a stigma and sense of inadequacy (17, 18). Moreover, a study from 2017 shows that close relatives feel it is a burden to have to provide care in the home and that it is crucial that they get social support from their social network and from the employees in the health and care services (19).

There is insufficient knowledge about the significance of close relatives and their role in the allocation of long-term nursing home beds. In this article, we therefore contribute to new knowledge in an under-examined area. The article is a part of a larger study that aims to explore which factors are given weight in the allocation of long-term nursing home beds among other things.

Method

The study has a qualitative and exploratory design that uses individual interviews and observations as methods. The interviews and observations were conducted in spring 2017.

Context

Four municipalities – one large, two mid-sized and one small – were included in the study. The mid-sized municipalities had 25 000–35 000 residents, and the small municipality had about 5000 residents. The largest municipality was divided into urban districts.

All the municipalities had short-term wards for patients who needed a shorter stay in a nursing home. The patients on the short-term wards could come from home or from the hospital where their treatment was considered to be finished.

The municipalities had an allocation office that was responsible for allocating services. In most municipalities, the allocation offices have weekly meetings with employees from the short-term wards. The municipalities were strategically selected. We wanted to include municipalities of different sizes and with various ways of organising the health and care services.

Individual interviews

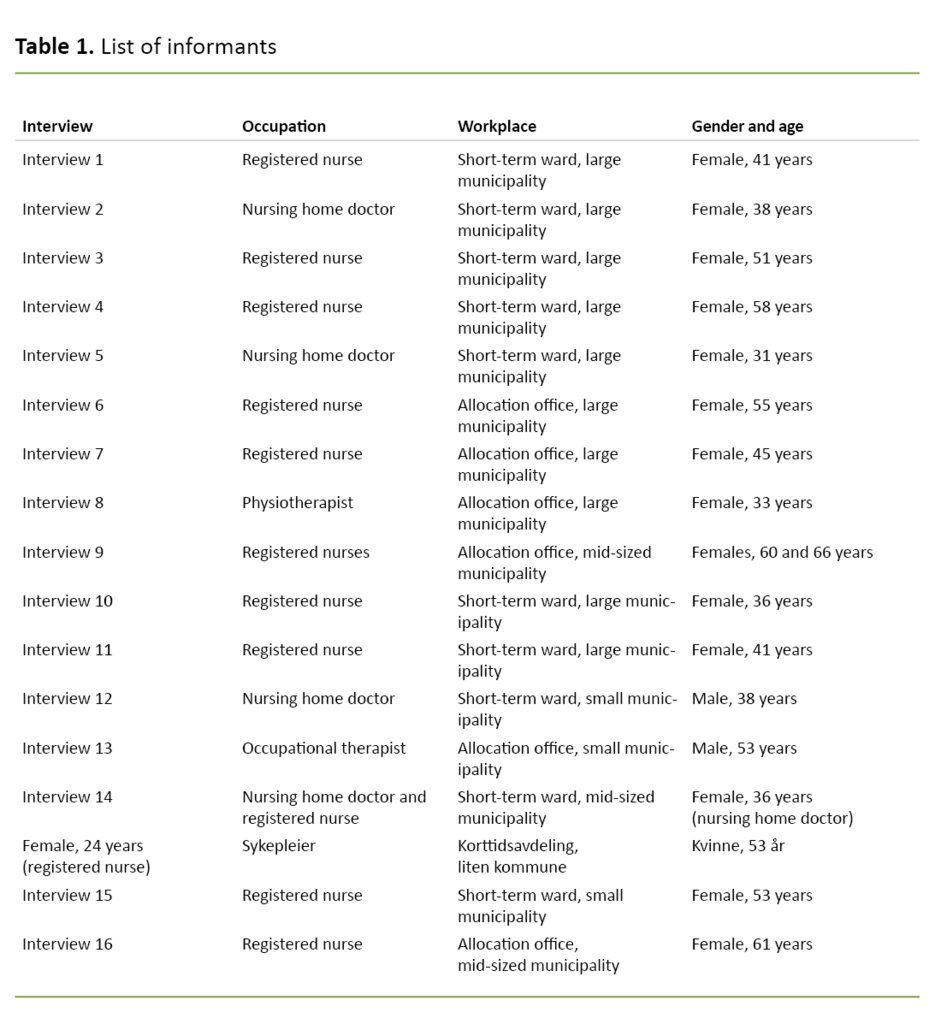

We interviewed seven case officers in the allocation offices. Five of them were registered nurses (RN), one was a physiotherapist and one was an occupational therapist. We also interviewed four doctors and seven RNs on four different short-term wards (Table 1). To highlight different perspectives, it was important to include participants from both the allocation side and the practitioner side. The most important criterion was that the informants had experience with the allocation process.

We contacted the directors of nursing homes that had short-term wards and heads of the allocation offices. The managers conveyed the information about the project to the employees, who then reported their interest to their manager. The interviews were based on a semi-structured thematic guide, primarily with open-ended questions, to ensure that the responses were as robust as possible so that we would not simply have our preconceptions confirmed.

We asked the informants to describe the process whereby the patient is allocated a long-term nursing home bed and how they felt about the process. They were also asked which criteria they thought should be used to ensure the allocation was fair. During the interview, we asked follow-up questions, either to delve deeper into what the informant said or to clarify whether we had correctly understood the informants.

The lead author conducted the interviews in a meeting room at the informants’ workplace. The interviews, which lasted from 1 to 1.5 hours, were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Observations

The lead author took part in 13 meetings in which allocation of services was discussed. The meeting participants included case officers from the allocation offices, RNs, doctors, occupational therapists and physiotherapists. The meetings lasted from 30 minutes to one hour.

The lead author took field notes from the meetings, paying special attention to the discussions between the employees about which patients should be allocated a bed after completing a stay on the short-term ward. More informal conversations with the participants took place before and after the meetings, and these conversations were also transcribed.

Analysis

We conducted a thematic content analysis in keeping with Braun and Clarke’s six-step method (20) in which researchers 1) familiarise themselves with the data, 2) assign preliminary codes to the data, 3) search for themes, 4) evaluate the themes, 5) define and name the themes, and 6) produce the report.

In the first step, we read through the interviews and field notes to familiarise ourselves with the material. In the next step, we generated introductory codes, then searched for sub-themes (step 3). Then we came together to evaluate, define and name the sub-themes, which could then be categorised under the main themes (steps 4–5).

The sub-themes that emerged were ‘Close relatives as the driving force’ and ‘Close relatives as buffers’. These sub-themes were consolidated under the main theme ‘The role of close relatives in the allocation process’.

Research ethics

The project was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (project number 50483). In addition, the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics granted an exemption from the duty of confidentiality so that we could take part in meetings where patient information was shared (project number 2016/1978).

All the participants gave their informed consent in writing. The participants were told that they could withdraw from the study at any time without providing a reason.

The authors’ background and preconceptions

The lead author is an RN with experience from research related to nursing homes, but not from home-based services or allocation processes. The second author, who is a doctor and professor of medical ethics, participated in a previous study on the home care service which showed, among other things, that resourceful relatives can contribute to an unfair allocation of care services (10).

The fact that we as researchers knew that close relatives can often influence the allocation of treatment and services was a part of our preconceptions.

Results

The informants said they felt that close relatives had an important role in the allocation of services in general, but especially in connection with the allocation of long-term nursing home beds. The crucial role of close relatives was confirmed in the meetings between the allocation offices and staff on the short-term wards.

On one hand, the informants explained that close relatives could function as the driving force behind the allocation of long-term beds. On the other hand, many close relatives acted as ‘buffers’ in the system so that the patient could live at home longer.

Close relatives as the driving force

‘Yes, it’s a topic of discussion that resourceful relatives are in the driver’s seat. If you have relatives who persist and set their foot down and say “this is not acceptable to me” and cite laws and such, then you are well on your way to getting a permanent bed’ (interview 1, RN, short-term ward in the large municipality).

It became clear that resourceful adult children are often the strongest driving force behind bed allocation. The participants said that close relatives could not only play a crucial role in whether a patient received a long-term nursing home bed, but that they could also influence how quickly a patient got a bed.

It became clear that resourceful adult children are often the strongest driving force behind bed allocation.

Although the case officers were concerned that all other services were tried out before a long-term nursing home bed was allocated, the informants explained that close relatives sometimes applied pressure so that the patient went directly from a short-term stay to a long-term bed in a nursing home.

If close relatives were not able to influence the allocation office, they often reached further up into the system: to the municipality’s chief administrative officer and sometimes also to the county governor. Several informants said that the fear that relatives might subsequently contact the media could influence the allocation process.

One of the case officers said that close relatives often got support if they complained to the county governor. The case officers also described how urban districts with many resourceful relatives often had to ‘give in’ when the relatives appealed a formal administrative decision.

The interviews and field notes showed how vulnerable patients were if they did not have close relatives. Sometimes the needs of patients who were alone were identified completely by accident or they had even ended up in hospital before their need for help was discovered.

‘Before the district meeting, I was sitting and talking with a case officer. We talked about the significance of having close relatives, that they were important. I asked how those who did not have close relatives were identified by the system. She said that it often happened by accident. She mentioned a patient with cancer who they did not learn about until she was hospitalised. Although she had an enormous need for nursing and care services, she was not found by the system until she became seriously ill’ (field notes from the large municipality).

The interviews and field notes showed how vulnerable patients were if they did not have close relatives.

All the informants thought it was problematic when patients with resourceful relatives were given priority over those who had no one to advocate for them. Doctors and RNs on short-term wards in particular described how they assumed the role of spokesperson for those without close relatives:

‘Yes, I kind of get into the fighting spirit on behalf of people without close relatives. I get that way, sure, but then I can be an advocate for them’ (interview 14, RN, short-term ward in a mid-sized municipality).

Close relatives as buffers

However, close relatives were not only the driving force behind bed allocation. Many of them wanted to have their family member at home and would go to great lengths to provide care if the patient did not want a nursing home bed:

‘There are lots of spouses who keep pushing and pushing themselves until they hit a wall’ (interview 9, case officer in a mid-sized municipality).

In a meeting between the short-term ward and a case officer in the large municipality, it came to light that close relatives could sometimes cause the patient to receive less than satisfactory care. One example of this was a son who wanted his father, after a short-term stay, to try living at home a little longer. One week later, in a meeting with case officers and employees on the short-term ward, it was learned that the patient had returned to the short-term ward when it became clear that it was irresponsible to have the patient at home.

In situations where close relatives could not manage anymore, a nursing home bed was often approved quickly.

Some close relatives, such as spouses, were able to meet the patient’s care needs, but they would ultimately ‘break down’. In situations where close relatives could not manage anymore, a nursing home bed was often approved quickly.

To relieve the close relatives and prevent them from ‘hitting a wall’, the urban district or municipality could arrange a respite stay for the patient, which postponed the need for a long-term bed. However, the care required by the patient living at home could be just on the limit of what the relatives could manage:

‘Case officers and employees discuss a patient who has a temporary placement on the short-term ward. They say that the wife is totally worn out and that she sobbed when he came in yesterday. She has waited so long for a temporary placement. “Soon we will have two patients instead of one,” said an RN. The case officer said they will see how it goes’ (field notes from the large municipality).

Last but not least, the employees were interested in having close relatives as collaborative partners. The relatives knew the patient best and were important when assessing the patient’s need for a nursing home bed:

‘When you get into that situation, close relatives are extremely important. Important not least to get an overview of how they assess the situation, of what they have experienced. They are often the ones in the midst of the situation and see the person who needs a nursing home bed on a daily basis (interview 13, case officer in the small municipality).

Discussion

Findings from our study and similar studies show that close relatives play an important role in the allocation and provision of municipal health and care services. They function as buffers and caregivers, but they are also the driving force when health and care services are allocated (15, 21).

When some patients more easily receive a nursing home bed due to the efforts of their resourceful relatives, other patients pay the price. Patients who do not have close relatives and who need a nursing home bed may have less of a chance of getting a bed, and thus become particularly vulnerable. This is an ethical problem and it challenges the fundamental principle that everyone has the right to equal access to health and care services. This problem comes to light in other studies as well (15, 22).

A previous article from our study showed that the municipalities largely use the same criteria for allocating nursing home beds, but that there are nonetheless large variations (23). To ensure a fair allocation of services, transparency around the services that are available is crucial. Moreover, the guidelines on service allocation must be clear to both the patients and their close relatives (15, 23).

Close relatives can uncover system failures

Close relatives that complain about or put pressure on the system can, however, reveal that patients are not getting the health care they need and have a right to, and that public service providers take too long to enter the picture. A study of 83 elderly people living at home in Oslo confirms that many very old people in great need of health and care services do not receive the necessary health care (24).

The voice of close relatives is crucial in order to uncover such system failures and to make improvements in the system and the services. An overall improvement of the system and services will benefit all service recipients, including those who do not have close relatives.

Our informants describe how close relatives often go to great lengths to provide care. Recent political guidelines state that families must help out to ensure that the health and care services are adequate and that the voluntary and philanthropic sector must provide more assistance (6). Both our findings and the political guidelines are in keeping with the political mantra that ‘everyone shall live at home’ (25).

Our informants describe how close relatives often go to great lengths to provide care.

Basic health and care services in the Norwegian welfare state will face challenges over time as the new generation of elderly develops a need for nursing and care services. Therefore, it can be both important and necessary for close relatives to be a resource for their family members. Since close relatives often know the patient better than the nursing home staff, they can help to ensure that the patients are able to live their lives more in keeping with their own values and wishes (26).

Patients may also have their relational and emotional needs met in a more satisfactory manner (27). When close relatives help out their family members, this can increase the resources that healthcare staff have to use on other services or other patients (15).

If there is a need, and the political will, for close relatives to help out, it is crucial that they receive the necessary guidance and support from healthcare staff (18, 19). In addition, it has been shown that good respite services, such as a safe and secure short-term nursing home stay, are critical in order for close relatives to keep going and for the patient to be able to live at home longer (18).

Can close relatives provide proper care?

However, not all close relatives can or want to help out as caregivers. When this happens under strong pressure from outside, it must be assumed that the ‘care’ provided is not always what is best for the patients. It is therefore crucial that close relatives are allowed to set boundaries for what care tasks they take upon themselves (26).

The law emphasises that health and care services are to be provided in a responsible and caring manner (28). When close relatives assume tasks related to caregiving, the question arises as to where the line is drawn when it is no longer justifiable for them to carry out those tasks. Nor can close relatives be expected to perform tasks that professionals are trained to do.

Previous research shows that there are no systems and guidelines for how close relatives should be involved and taken care of (27, 29). If close relatives are to have responsibility for caregiving tasks, some clear guidelines should be drawn up that define the responsibilities of close relatives versus those of the public authorities.

By law, close relatives must also be informed about the municipality’s legally required services (1). In addition, there should be a quality-assurance system ensuring that relatives do not perform tasks that they are medically unqualified for.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The findings in the study cannot be generalised, but are highly relevant for the health services in general and for the development of services for the elderly in particular. We believe that the findings will be familiar to employees in the municipal health services and to patients and their close relatives who are affected by these services.

A strength of the study is that the results we present are found in all four of the municipalities, in both interviews and field notes. However, there will be a need for more studies that can support the findings.

A weakness of the study is that we did not interview the close relatives themselves or employees in home-based services about how they experience the allocation process. If we had done so, we would have gained knowledge from multiple perspectives, including knowledge of the relatives’ needs. This will be relevant to explore in future studies.

Conclusion

Our study shows that close relatives have an important role in the allocation of long-term nursing home beds, for both good and bad. On the one hand, they are a vital resource in the welfare state because they help patients to live at home longer.

On the other hand, they can be seen as the driving force behind the allocation of services. This in turn can make the allocation processes unfair since service allocation should not depend on whether or not a patient has resourceful relatives.

Our findings show that it is important to have transparent allocation processes and an additional focus on patients who do not have close relatives with substantial resources. At the same time, resourceful relatives can identify weaknesses in the system. With the challenges facing the welfare state, close relatives are a vital resource.

What is needed, however, is an open discussion about the role that close relatives can and should have in health and care services in the future. It is necessary to have a system that ensures relatives are involved and taken care of in the best way possible.

References

1. Lov 24. juni 2011 nr. 30 om kommunale helse- og omsorgstjenester m.m. (helse- og omsorgstjenesteloven). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2011-06-24-30/ (downloaded 04.03.2021 ).

2. Tønnessen S, Kassah BLL. Pårørende til pasienter og brukere i kommunale helse- og omsorgstjenester. In: Tønnessen S, Kassah BLL, eds. Pårørende i kommunale helse- og omsorgstjenester. Forpliktelser og ansvar i et utydelig landskap. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2017. pp. 16–27.

3. Gautun H, Grødem AS. Prioritising care services: Do the oldest users lose out? International Journal of Social Welfare. 2015;24(1):73–80.

4. Gautun H, Grødem AS, Hermansen Å. Hvordan fordele omsorg? Utfordringer med å prioritere mellom eldre og yngre brukere. Oslo: Fafo; 2012.

5. Gautun H, Syse A. Earlier hospital discharge: a challenge for Norwegian municipalities. Nordic Journal of Social Research. 2017;8. DOI: 10.7577/njsr.2204

6. Meld. St. 29 (2012–2013). Morgendagens omsorg. Oslo: Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet; 2013.

7. Daatland SO, Otnes B. Institusjon eller omsorgsbolig? Skandinaviske trender i eldreomsorgen. Samfunnsspeilet. 2015(3):15–22. Available at: https://www.ssb.no/helse/artikler-og-publikasjoner/institusjon-eller-omsorgsbolig (downloaded 04.03.2021).

8. Fjelltun AS, Henriksen N, Norberg A, Gilje F, Normann HK. Nurses' and carers' appraisals of workload in care of frail elderly awaiting nursing home placement. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2009;23(1):57–66.

9. Palmer JL, Langan JC, Krampe J, Krieger M, Lorenz RA, Schneider JK, et al. A model of risk reduction for older adults vulnerable to nursing home placement. Research & Theory for Nursing Practice. 2014;28(2):162–92.

10. Tønnessen S. The challenge to provide sound and diligent care: a qualitative study of nurses' decisions about prioritization and patients' experiences of the home nursing service [Doctoral Dissertation]. Oslo: Det medisinske fakultet, University of Oslo; 2011.

11. Tønnessen S. Påørende: usynlige bærebjelker i velferdsstaten. In: Vike H, Debesay J, Haukelien H, eds. Tilbakeblikk på velferdsstaten. Politikk, styring og tjeneste. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2016. pp. 76–97.

12. Andersen KL, Strøm A, Korneliussen K, Fagermoen MS. Pårørende til hjemmeboende med hjertesvikt: «medarbeidere» i ukjent tjenesteterreng. Sykepleien Forskning. 2016;11(2):(158–65). DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2016.57818

13. Strøm A, Andersen KL, Korneliussen K, Fagermoen MS. Being «on the alert» and «a forced volunteer»: a qualitative study of the invisible care provided by the next of kin of patients with chronic heart failure. J Multidiscip Healthc. Jun. 2015;2015:271–7. DOI: 10.2147/JMDH.S82239

14. Anker-Hansen C, Skovdahl K, McCormack B, Tonnessen S. Invisible cornerstones. A hermeneutic study of the experience of care partners of older people with mental health problems in home care services. Int J Older People Nurs. 2019;14(1):e12214. DOI: 10.1111/opn.12214

15. Tønnessen S, Førde R, Nortvedt P. Fair nursing care when resources are limited: the role of patients and family members in Norwegian home-based services. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice. 2009;10(4):276–84.

16. Carlsen B, Lundberg K. ‘If it weren't for me …’. Perspectives of family carers of older people receiving professional care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2018;32(1):213–21.

17. Cottrell L, Duggleby W, Ploeg J, McAiney C, Peacock S, Ghosh S, et al. Using focus groups to explore caregiver transitions and needs after placement of family members living with dementia in 24-hour care homes. Aging & Mental Health. 2020;24(2):227–32.

18. Berglund A-L, Johansson IS. Family caregivers' daily life caring for a spouse and utilizing respite care in the community. Vård i Norden. 2013;33(1):30–4. DOI: 10.1177/010740831303300107

19. Wold KB, Rosvold E, Tønnessen S. «Jeg må bare holde ut …». Pårørendes opplevelse av å være omsorgsgiver for hjemmeboende kronisk syke pasienter – en litteraturstudie. In: Tønnessen S, Kassah BLL, eds. Pårørende i kommunale helse- og omsorgstjenester. Forpliktelser og ansvar i et utydelig landskap. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2017. pp. 52–78.

20. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101.

21. Anker-Hansen C, Skovdahl K, McCormack B, Tønnessen S. Invisible cornerstones. A hermeneutic study of the experience of care partners of older people with mental health problems in home care services. Int J Older People Nurs. Mar. 2019;14(1):e12214. DOI: 10.1111/opn.12214

22. Syse A, Øien H, Solheim MB, Jakobsson N. Variasjoner i kommunale tildelingsvurderinger av helse- og omsorgstjenester til eldre. Tidsskrift for velferdsforkning. 2015;18(3):211–33.

23. Heggestad AKT, Førde R, Heggestad AKT. Is allocation of nursing home placement in Norway just? Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2020;34(4):871–9. DOI: 10.1111/scs.12792

24. Næss G, Kirkevold M, Hammer W, Straand J, Wyller TB, Næss G. Nursing care needs and services utilised by home-dwelling elderly with complex health problems: observational study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:artikkelnr. 645. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-017-2600-x

25. Daatland SO, Høyland K. Boliggjøring av eldreomsorgen? Oslo: Velferdsforskningsinstituttet NOVA; 2014.

26. Rønning R, Johansen V, Schanke T. Frivillighetens muligheter i eldreomsorgen. Lillehammer: Østlandsforskning; 2009. ØF-rapport nr. 11/2009. Available at: https://www.ostforsk.no/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/112009.pdf (downloaded 04.03.2021).

27. Aasgaard HS, Disch PG, Fagerström L, Landmark BT. Pårørende til aleneboende personer med demens – Erfaringer fra samarbeid med hjemmetjenesten etter ny organisering. Nordisk sygeplejeforskning. 2014;4(2):114–28.

28. Lov 2. juli 1999 nr. 64 om helsepersonell m.v. (helsepersonelloven). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-64 (downloaded 04.03.2021).

29. Fjose M, Eilertsen G, Kirkevold M, Grov EK. «Non-palliative care» – a qualitative study of older cancer patients’ and their family members’ experiences with the health care system. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:artikkelnr. 745. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-018-3548-1

Comments