‘Existential care’ in Bachelor of Nursing programmes – a document analysis

The subject is incorporated into programme descriptions, course plans and reading lists. However, learning outcome descriptors would benefit from being more precise and easier to verify.

Background: Registered nurses (RNs) encounter patients whose ability to handle existential challenges is significantly influenced by the RNs’ knowledge and skills in existential care. Norwegian health and education authorities expect RNs to have the necessary qualifications to tend to their patients’ existential needs. It is therefore essential that the courses in Norwegian Bachelor of Nursing programmes meet these expectations.

Objective: The study’s objective is to describe the extent to which existential care is specifically addressed in the programme descriptions, course plans and reading lists of Norwegian Bachelor of Nursing programmes.

Method: We conducted a summative content analysis of the programme descriptions and course plans produced by the 13 educational institutions that offer Bachelor of Nursing programmes. The analysis sought to investigate the occurrence of ‘existential care’ as a subject, and how it is referred to in these documents.

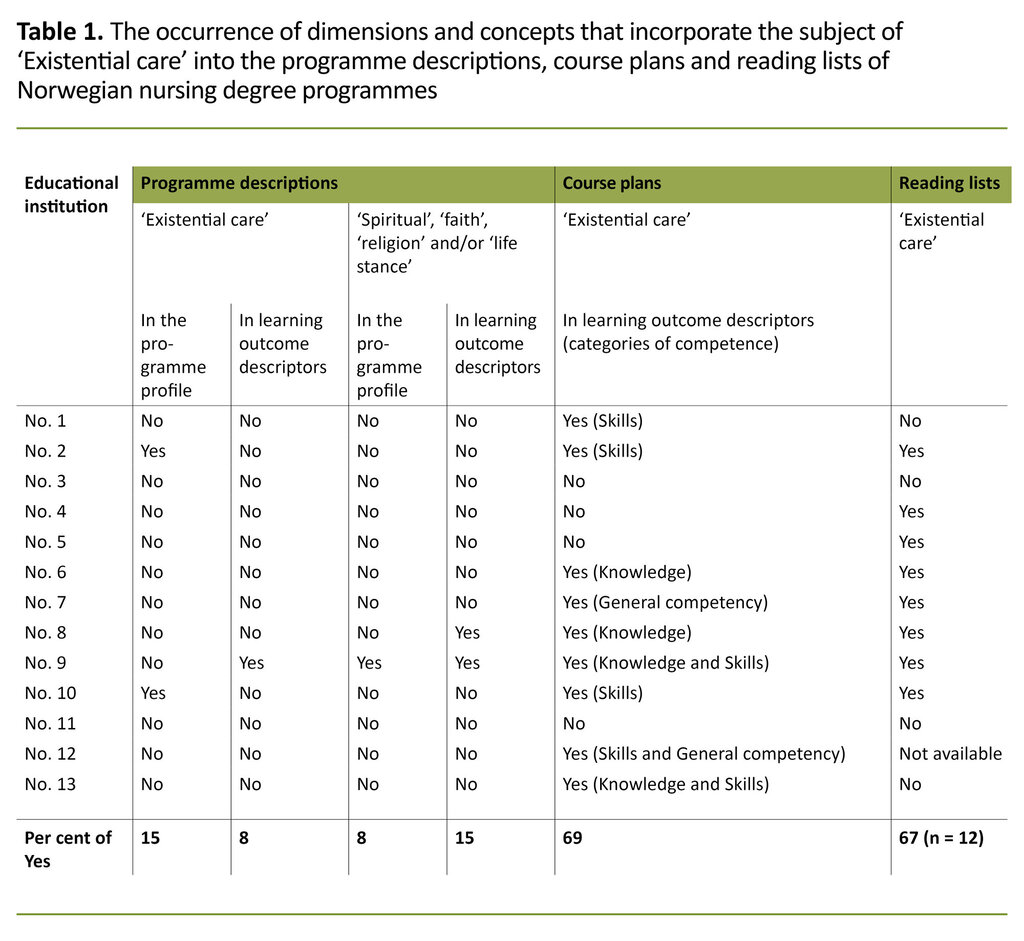

Results: Existential care was specifically mentioned in nine of the thirteen education programmes (69 per cent). Eight education programmes (67 per cent) included ‘existential care’ and/or ‘spiritual care’ as a subject in their reading list, while a far lower percentage included it in their programme descriptions (15 per cent) and learning outcome descriptors (8 per cent). The general trend was for competency requirements to be linked to ‘practical skills’, while it was linked to ‘knowledge’ and ‘general competency’ only to a lesser extent.

Conclusion: Existential care is well integrated into the programme descriptions, course plans and reading lists of Norwegian undergraduate nursing programmes. Learning outcome descriptors would however benefit from being more precise and easier to verify. There is also a need for the knowledge and skills aspects of the competency requirements to be given equal status. The new national guidelines for nursing education accommodate this need, which gives an even clearer signal that existential care must be an integral part of the education programmes.

Existential issues affect all human beings and they often come to the fore in life’s transition phases or during major life changes, when there is a threat to our own life or that of a loved one, or when our basic values are called into question. Serious illness and other critical situations often make these issues more pressing and acute (1–5).

The way that individuals handle existential questions and challenges is influenced by a combination of their personality and sociocultural circumstances as well as their religion and life stance (5). ‘Existential care’ is increasingly being used as a general, overarching concept in the field of health and social care, particularly in a Scandinavian context (6).

The health service often provides the contextual framework for emergencies and critical situations. Within this framework, existential care is provided by healthcare personnel as they respond to the patients’ need or wish to talk about their personal, existential challenges (4).

Awareness of the full range of existential needs and their individual variations, and of how these needs may be expressed, is an important premise for providing good existential care. Existential needs manifest themselves in numerous ways. They may be communicated through religiosity or spirituality, or they may take the form of resentment or opposition to religion or culture.

This means that the patient’s existential challenges, resources and needs can, albeit not necessarily, have a religious or spiritual dimension. Because the patient’s needs and form of expression are key, existential care is a far broader concept than religious or spiritual care (5, 6).

Registered nurses (RNs) are the group of healthcare personnel who most often encounter patients who want or need existential care. Providing such care requires not only knowledge about religions and life stances, and the various ways in which existential needs may be expressed, but also communication skills in interactions with patients (7–10).

It has been seen as a paradox (11) that despite the fact that providing existential care is universally accepted as an important part of an RN’s job (12), it is often marginalised in nursing education programmes (13). Also, RNs often feel that they are inadequately qualified to provide existential care for patients (14).

This paradox may be caused by a complex set of reasons. Providing existential care can be emotionally demanding (15), and a reluctance to take on such demanding tasks is understandable.

This reluctance is likely to be particularly common among those whose basic training has been inadequate in this area, as they will not feel confident in providing emotionally demanding care. Such reluctance can be amplified by working in a highly instrumentalised professional context, where overarching financial frameworks and resource priorities can leave little room and time for the reflexivity and reflection that is considered essential to providing good existential care (11).

Norway’s new regulations on the national guidelines for nursing education (16) state that nursing graduates will have knowledge of non-discriminatory care for all religions, genders and cultures and that this will facilitate and equal service provision for all groups in society. There is also a focus on ensuring that all interaction with individual patients and their families is based on respect, involvement in decision-making, and integrity.

Existential care and various forms of chaplaincy are also covered by the Government’s ‘dignity guarantee’ (17), which expects the primary health service to offer elderly people an opportunity to talk about existential questions. Chaplaincy involves making arrangements for patients to practice their religion or life stance, and receive visits from representatives of their own religious or life stance community.

Such general government guidelines create an expectation that all Norwegian nursing graduates have acquired, through their education, the knowledge and skills required to meet the existential needs of patients and their families.

The objective of the study

This study’s objective was to describe the extent to which existential care is specifically addressed in the programme descriptions, course plans and reading lists of Norwegian Bachelor of Nursing programmes.

Method

Data

Following the mergers of various university colleges in recent years, there are now 13 educational institutions that offer a Bachelor of Nursing programme, according to the national database for higher education (18). We obtained written permission from all of these institutions to investigate how existential care is thematised in their programme descriptions, course plans and reading lists for the 2018/19 academic year. We also studied their programme profiles, which are brief descriptions of overarching objectives, academic content and learning outcomes.

The new national guidelines for nursing education (15) came into force in 2020. However, the 2008 National Curriculum (19) still applies for second and third-year students, which is why this study is based on that curriculum. The documents were downloaded from the education programmes’ websites and the Leganto digital reading list system. Only one education programme did not have their reading lists available (Table 1).

Data analysis

The term ‘document’ refers to written sources available for analysis by the researcher (20). A document analysis is intended to show how overarching intentions are expressed in the data material. The objective is to identify important connections and relevant information about learning outcomes and knowledge (20, 21).

In this study, we chose to conduct a summative content analysis (22) in order to investigate whether existential care was addressed in the documents, and if so, how.

The analysis was conducted in three phases. We started by distributing the programme descriptions, course plans and reading lists among four of the authors, who each read all of the material in order to establish how ‘existential care’ was described. A wide variety of terms was used to refer to the subject, such as ‘spiritual’, ‘faith’, ‘life stance’ and ‘religion’. This necessitated a further read-through in order to include and systematise these terms in the analysis. To ensure analytic validity, all authors analysed the same documents from three of the education programmes.

We proceeded to present and discuss the results with the full group of authors. In the second phase, the results of the first read-through were systematised in order to establish the occurrence of the terms in the programme descriptions, course plans and reading lists. In the third phase, we grouped all the learning outcome descriptors that referred to the subject of ‘existential care’ into the competency categories that were used in programme descriptions and course plans.

Results

Existential care was thematised in nine of the thirteen education programmes (69 per cent) (Table 1). Eight education programmes (67 per cent) had included ‘existential care’ and/or ‘spiritual care’ as a subject in their reading lists, while a far lower percentage had included it in their programme descriptions (15 per cent) and learning outcome descriptors (8 per cent).

Existential care was thematised in nine of the thirteen education programmes.

Programme descriptions

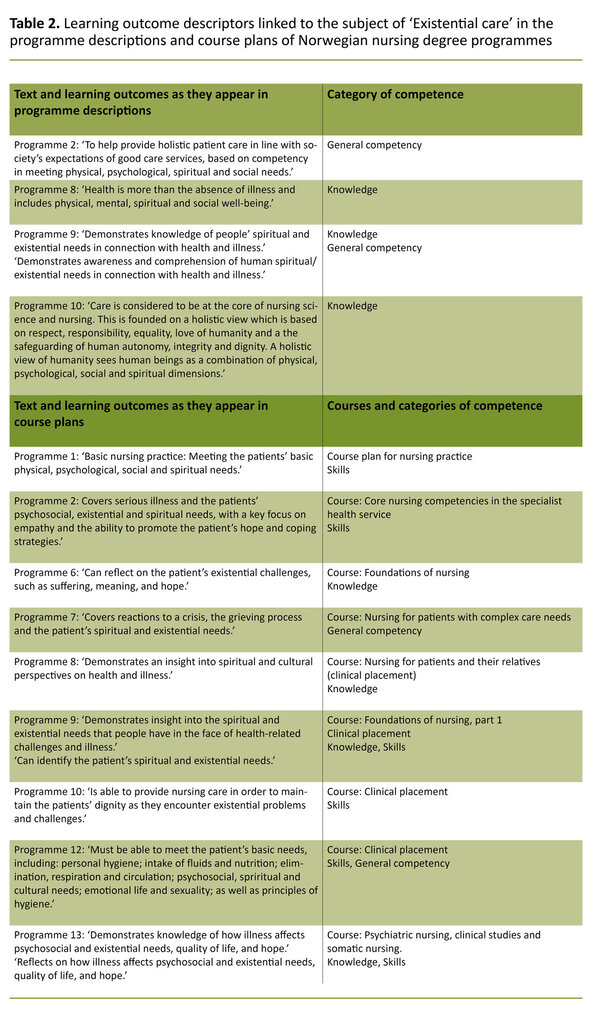

The four education programmes that used the terms ‘existential’ and/or ‘spiritual’ in their programme descriptions linked their learning outcomes to general competency and knowledge (Table 2).

Course plans

The various course plans referred to the subject of ‘existential care’ in different ways in order to describe the student’s nursing skills in existential care. Five of eight education programmes had course plans that used active verbs to describe the provision of existential care (‘meet’, ‘identify’, ‘conduct’ and ‘promote’). The course plans in the remaining three programmes included references to knowledge, insight and reflection on the issues (Table 2).

All of the education programmes that referred to the subject, linked it to clinical courses. The terms were used about general skills (practical nursing skills like meeting, identifying and promoting existential care) as well as general knowledge, comprehension and reflective capacity.

The reading lists

Although two education programmes (nos. 4 and 5) included no mention of ‘existential care’ in their programme descriptions and course plans, their reading lists nevertheless covered the subject and were relevant. Two of the programmes (nos. 3 and 11) that failed to mention the subject in their programme descriptions and course plans also failed to include existential care in their reading list.

The reading lists of six education programmes (nos. 2 and 6–10) that did use the terms in their programme descriptions and/or course plans also included set reading that dealt with ‘existential care’. Two education programmes (nos. 1 and 3) that mentioned the subject in their descriptions and plans did not refer to relevant set reading. We did not have access to the reading list for education programme no. 12.

Discussion

The study’s objective was to describe the extent to which existential care is specifically addressed in the programme descriptions, course plans and reading lists of Norwegian Bachelor of Nursing programmes.

There was a general tendency to categorise the competency requirements under ‘practical skills’ rather than under ‘knowledge’ and ‘general competency’. For example, the practical skills requirements included the ability to identify and meet the patient’s existential needs.

Learning to provide existential care in real clinical contexts falls within the educational concept of ‘situated learning’ (23). A Norwegian study has demonstrated the importance of situated learning in a setting where experienced ambulatory RNs provided instruction and guidance for other healthcare personnel in administering existential care in real-life clinical situations (24).

There was a general tendency to categorise the competency requirements under ‘practical skills’ rather than under ‘knowledge’ and ‘general competency’.

Situated learning can be challenging, for example in relation to instrumental procedures that are technically complicated. We maintain, however, that the human and relational aspects of learning to provide existential care make the challenge even greater. The learning process will be impacted by the student as well as the placement supervisor or teacher, and by the relationship between them. The quality of the skills that are learnt is therefore linked to the knowledge, attitudes, priorities and values of both parties (14, 25–27).

The quality can also suffer if the student and/or placement supervisor or teacher themselves have an indeterminate or problematic relationship with the existential issues that the patient might be grappling with. This may cause the patient’s needs to be inadequately met and ultimately even misinterpreted or ignored. One possible outcome may be that the students have dissimilar conditions of learning. ‘Situated learning’ (23) in a placement institution can therefore easily become privatised due to the education programmes’ limited opportunity to monitor whether challenges are addressed and learning objectives met.

There is no clear-cut distinction between ‘knowledge’, ‘general competency’ and ‘practical skills’ (28). We therefore need to keep in mind that categorising existential care under ‘skills’ may well be a somewhat random choice. However, if existential care is inadequately rooted in the ‘knowledge’ and ‘general competency’ categories, this can increase the risk of existential care being perceived as an instrumental skill. In light of practical clinical knowledge, accumulated over a long time, it appears nonetheless that this risk may well be minimal.

It is likely that the biggest challenge is fragmentation of teaching efforts in ‘existential care’, as this would deny the students the opportunity to integrate their relevant knowledge, general competency and skills in this area.

The question is therefore what elements of knowledge and general competency are needed to further such integration. With today’s diversity of religions and life stances in mind (29), the knowledge dimension could for example be linked to how the patient’s life stance and religiosity can be expressed in specific care settings. General communication and interaction competency is another example.

It is therefore reasonable to assume that all of the education programmes have a reading list that covers the subject to some extent.

There is also an opportunity to learn specific skills, for example by using the Cultural Formulation Interview (30), which is well suited to capturing the existential challenges and needs of individual patients in today’s multicultural society.

Two of the education programmes that mention ‘existential care’ in their descriptions and plans do not list any set reading on the subject. Nonetheless, it may still be a part of the syllabus because some foundation nursing textbooks cover existential and spiritual care in chapters about palliation and promoting the patient’s perception of meaning and hope. It is therefore reasonable to assume that all of the education programmes have a reading list that covers the subject to some extent.

Conclusion

This study has shown that existential care is currently well integrated into the programme descriptions, course plans and reading lists of Norway’s graduate nursing programmes. However, the study suggests that the programmes’ learning outcome descriptors may benefit from being more precise and easier to verify.

Also, the knowledge and skills dimensions of the programmes’ competency requirements should have equal status. The new national guidelines for nursing education accommodate such equal status (16) and give clear signals that existential care must be an integral part of graduate nursing education.

We are grateful for the critical review of the manuscript conducted by Trine-Lise Jansen who is a lecturer at Lovisenberg Diaconal University College and a PhD student at the MF Norwegian School of Theology, Religion and Society. Thanks also go to Nosrat Farhood Ghafarian RN, from Lovisenberg’s Cathinka Guldberg Centre, who assisted with our literature searches.

References

1. Yalom ID. Existential psychotherapy. Basic Books; 1980.

2. Balboni MJ, Sullivan A, Amobi A, Phelps AC, Gorman DP, Zollfrank A, et al. Why is spiritual care infrequent at the end of life? Spiritual care perceptions among patients, nurses, and physicians and the role of training. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(4):461–7.

3. Sørensen T. Religiøsitet, åndelighet og eksistensiell meningsdannelse. In: Dahl AA, ed. Kreftsykdom: psykologiske og sosiale perspektiver. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk; 2016. pp. 275–300.

4. Kompetansebroen. Eksistensiell omsorg. Available at: https://www.kompetansebroen.no/modul/eksistensiell-omsorg/?o=innlandet# (downloaded 10.06. 2020).

5. Stifoss-Hanssen H, Kallenberg K. Livssyn og helse. Teoretiske og kliniske perspektiver. Oslo: Ad Notam Gyldendal; 1998.

6. Rykkje L, Austad A, eds. Eksistensielle begreper i helse- og sosialfaglig praksis. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 2020.

7. Sinclair S, Bouchal SR, Chochinov H, Hagen N, McClement S. Spiritual care: how to do it. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. 2012;2(4):319–27.

8. Pesut B. There be dragons: effects of unexplored religion on nurses’ competence in spiritual care. Nurs Inq. 2016;23(3):191–9.

9. Swinton J, Pattison S. Moving beyond clarity: towards a thin, vague, and useful understanding of spirituality in nursing care. Nurs Philos. 2010;11(4):226–37.

10. Baldacchino D. Spiritual care education of health care professionals. Religions. 2015; 6(2):594–613.

11. Carr TJ. Facing existential realities: exploring barriers and challenges to spiritual nursing care. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(10):1379–92.

12. Ross L. Spiritual care in nursing: an overview of the research to date. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15(7):852–62.

13. Ali G, Snowden, M, Wattis J, Rogers M. Spirituality in nursing education: knowledge and practice gaps. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Comparative Studies. 2018;5(1–3):27–49.

14. McEwen M. Analysis of spirituality content in nursing textbooks. J Nurs Educ. 2004;43(1):20–30.

15. Tornøe KA, Danbolt LJ, Kvigne K, Sørlie V. The challenge of consolation: nurses’ experiences with spiritual and existential care for the dying – a phenomenological hermeneutical study. BMC Nurs. 2015;14(1):62.

16. Forskrift 15. mars 2019 nr. 412 om nasjonal retningslinje for sykepleierutdanning. Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2019-03-15-412 (downloaded 30.06.2020).

17. Forskrift 12. november 2010 nr. 1426 om en verdig eldreomsorg (verdighetsgarantien). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2010-11-12-1426?q=Verdighetsgarantien (downloaded 30.06.2020).

18. Direktoratet for høyere utdanning og kompetanse. Database for statistikk om høyere utdanning. Bergen: Direktoratet for høyere utdanning og kompetanse; 2021. Available at: https://dbh.nsd.uib.no/omdbh/index.action (downloaded 27.03.2019).

19. Forskrift 25. januar 2008 nr. 128 til rammeplan for sykepleierutdanningen. Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2008-01-25-128?q=Rammeplan%20for%20sykepleierutdanningen%202008 (downloaded 30.06.2020).

20. Thagaard T. Systematikk og innlevelse: en innføring i kvalitative metoder. 5th ed. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget; 2018.

21. Grønmo S. Samfunnsvitenskapelige metoder. 2nd ed. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget; 2016.

22. Fauskanger J, Mosvold R. Innholdsanalysens muligheter i utdanningsforskning. Nor Ped Tidsskr. 2014;98(02):127–39.

23. Lave J, Wenger E. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991.

24. Tornøe KA, Danbolt LJ, Kvigne K, Sørlie VA. A mobile hospice nurse teaching teams’ experience: training care workers in spiritual and existential care for the dying – a qualitative study. BMC Pall Care. 2015;14:artikkelnr. 43. DOI: 10.1186/s12904-015-0042-y

25. Leenderts TA. Person og profesjon: om menneskesyn og livsverdier i offentlig omsorg. 3rd ed. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2014.

26. Peternelj‐Taylor CA, Yonge O. Exploring boundaries in the nurse‐client relationship: professional roles and responsibilities. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2003;39(2):55–66.

27. Alvsvåg H. Har sykepleien fortsatt en framtid? In: Andersen AJW, Larsen IB, Søderhamn O, eds. Utdanning til omsorg i fortid, nåtid og framtid. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2010. pp. 76–90.

28. Öhlen J. Practical wisdom: competencies required in alleviating suffering in palliative care. J Palliat Care. 2001;18(4):293–9.

29. NOU 2013: 1. Det livssynsåpne samfunn – En helhetlig tros- og livssynspolitikk. Oslo: Departementenes servicesenter, Informasjonsforvaltning; 2013. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/nou-2013-1/id711212/ (downloaded 15.06.2020).

30. Nasjonalt kompetansesenter for migrasjons- og minoritetshelse (NAKMI), Nasjonal kompetansetjeneste ROP. Kulturformuleringsintervjuet. Et klinisk verktøy i tverrkulturell kommunikasjon [Internet]. Oslo: Folkehelseinstituttet; 02.03.2015 [updated 02.03.2018, cited 30.06.2020]. Available at: https://www.fhi.no/publ/2015/kulturformuleringsintervjuet-cfi-dsm-5/

Comments