Family caregivers to a patient with chronic heart failure living at home: «co-workers» in a blurred health care system

Family caregivers will need correct and relevant information and support from health care professionals to perform the significant caring role they have to take on.

Background: Support from relatives is an important factor in how well people with heart failure manage their illness and daily living. Family members are expected to assume a greater role in the health care system. Health care professionals need knowledge on family members’ experiences and needs.

Objective: To explore experiences and views of family caregivers of heart failure patients with regard to their need for knowledge, support and collaboration with health care professionals.

Method: The study had an exploratory design with qualitative interviews of nineteen family members recruited from Heart Failure outpatient clinics and home care services. Thematic cross-case content analyses were performed.

Results: Three main themes were revealed:

- The family members’ involvement in illness management and information needs.

- A blurred health care system with insufficient information.

- The importance of support from available and competent health care professionals.

Conclusion: Family caregivers will need correct and relevant information and support from health care professionals to perform the significant caring role they have to take on. Increased focus on collaboration and expertise in municipal services has the potential to improve the situation for both patient and family.

Introduction

Heart failure is one of the most common causes of hospital admissions and readmissions in the older part of the population, and more than 100 000 persons in Norway are diagnosed with heart failure (1). This burden of illness is visible in the registration of more than 10 000 hospital admissions in Norwegian hospitals in 2012 due to heart failure (1,2). Heart failure is a serious and complex condition with symptoms such as breathing difficulties, exhaustion and swollen ankles, often resulting in a reduction in quality of life and many hospital admissions (3, 4).

Support from family and friends is significant to how persons with heart failure who live at home manage their illness, and reports show that eight out of ten close family members participate in illness-related tasks (5). Knowledge is important in order to act adequately, and studies show that family caregivers desire information on challenging areas such as dietary restrictions, mental state and signs and symptoms of change in the heart failure condition (6-8). They also wish to collaborate with the health services. Studies show that support from family members can reduce the number of hospital admissions and influence the outcome of the disease (9, 10). Other studies show that heart failure patients’ family caregivers have not received sufficient information at the time of discharge from hospital (5, 11).

The role of family caregivers has received increased attention and has been accorded a key role in the health and care services of the future, both as a care resource and as a source of knowledge (12). Informal caregivers will thus need knowledge, transmitted in the form of advice, guidance and training (13). The essence of the reform of the Norwegian health services (12) introduced January 1 2012, is a shift of tasks and responsibilities from hospital to municipality. It is reasonable to assume that this also affects the role of informal caregivers. We have not found any studies focussing on the family caregivers of heart failure patients after the collaboration reform was introduced.

The purpose of the study was to obtain knowledge on experiences and views of family caregivers of heart failure patients living at home, and the competence and support the caregivers need to manage the situation of their close ones and their own. The article will attempt to answer the research question «What characterises family caregivers’ experiences with collaboration with the health services?»

We have earlier published an article exploring the experiences of family caregivers with invisible care, such as being prepared and being involuntary volunteers (14).

Method

The study has an explorative qualitative design using interviews to collect data. Family members of heart failure patients were recruited from three heart failure outpatient clinics and three home care services districts with the following inclusion criteria:

- that the patient was in regular touch with his or her family member, preferably living together

- that the patient was competent to consent

- that the patient mastered the Norwegian language

Nurses who knew patients with heart failure gave oral and written information to both family and patient. We considered consent from the patient necessary to interview family, and all patients gave their consent. All family members who were asked consented to participation in the study. A total 19 family members were interviewed, 14 recruited in a heart failure outpatient clinic and five from the home care services. The majority chose to be interviewed in their homes, some in the researcher’s office or some other shielded place. The age span was 45 – 83 years (median 63). 17 were women, 12 married or cohabiting, and seven were daughters not living with the patient.

The interviews were carried out as conversations on open themes. We audio-recorded the interviews, done over the course of six months in 2013, and transcribed them. The conversations centred around the family member’s knowledge of heart failure and treatments of heart failure, the experience of confidence in the role of family caregiver, experiences with invisible care and care activities, need for practical and psychosocial support and need for training and counselling and guidance. This article treats findings linked to the two latter themes.

Data analysis

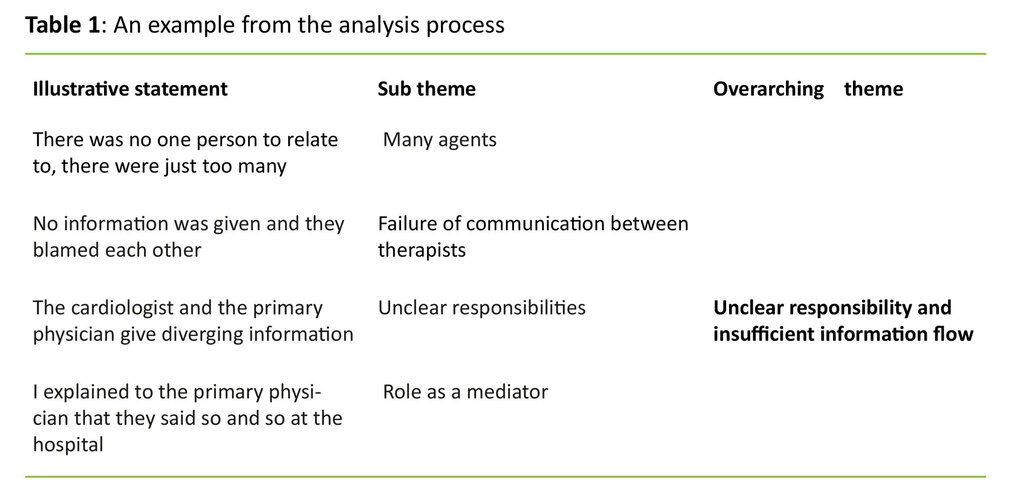

The study has an experience-oriented and interpretive approach. The processes of analysis are inspired by systematic text condensation (15,16). First, each researcher did an open reading of all interviews and wrote down a summary for each individual interview in order to form a holistic impression. Next, the researchers collectively performed the first open thematic analysis in order to identify preliminary themes. With this as a basis meaning-carrying units were identified, grouped, condensed and abstracted for each interview. The research group subsequently did a cross-case analysis of the interviews to identify overarching themes and subthemes. Table 1 shows an example of the analysis process.

Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) approved the study (31564/ 09 26 2012). The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki’s ethical principles for research.

Findings

The interviews reflected family members’ experience of responsibility, need for more knowledge and experiences in encounters with the health services.

In this article we explore the following themes:

- involvement, willingness to assume responsibility and desire for knowledge

- unclear responsibility and insufficient flow of information

- available and competent supporters

The first theme is about family members as active participants in the management of the illness and their desire and need for knowledge. The second theme is about their encounter with the complexities and unclear collaboration in the health services, and the last theme explores family members’ experiences with, and the significance of, having competent supporters in the health services.

1) Involvement, willingness to assume responsibility and desire for knowledge

Family caregivers described a daily routine with strong involvement in daily tasks related to the illness, with follow-up of treatment, handling of medication and assessment of whether the illness changed character. The majority referred to themselves as «co-walkers» and resource persons in relation to the illness. One family caregiver used the term «playing on the same team as» the partner. Several said they came along to examinations, treatments and controls. They expressed a wish and need to assume responsibility; participation was important for their own sake and linked to both internal and external expectations. One family member said: «He (the patient) really wants us to accompany him to the doctor and to everything. It is quite all right that we care about this and that». Another said she wrote down all information and everything that happened: «I have a phone where I enter everything and know exactly what to say to move on … I go along all the time to doctor’s appointments and look after for medications and such.» Several family members described concrete situations where they participated actively. “When he became ill and was admitted to hospital, of course I had to be there all the time to watch out for him”.

One common feature was the wish for continuous information. Several family members described the need for sufficient knowledge on symptoms of a worsening of the heart condition, so that they could react and act adequately when the patient’s situation changed. Several family members said that good and factual information was important to them. One respondent said: «Proper information and whether there are some symptoms that I should respond to … so that I can respond». Information on the treatment and medication was also important. They described situations where they felt insecure, where they felt that information and insight into the situation would have made them more confident. One family caregiver put it like this: «I have been really scared of more changes, also due to insufficient information … (I do not know) what is dangerous and what is not». Another respondent described it like this: «Really good and to the point information would have calmed me down».

Several family members described situations where they were not given sufficient information. They talked about situations where they felt like a nuisance – where health personnel were too busy and did not seem to have enough time to inform. The medical terminology used was also a challenge to some. One respondent described the experience thus: «We have to nag about everything to get an answer, and then they give us these doctors’ statements … I say speak Norwegian, so I can understand, I really do want to have it expressed». The search for information gave some family members an active role with clear strategies and preparedness in the encounter with health workers. One family caregiver described it as follows: «Sometimes when he is discharged (from hospital), I have written a note, and then I have been given answers, but then he (the doctor) is on the phone and the next patient is waiting … then you feel it is all a bit too quick».

2) Unclear responsibility and insufficient flow of information

Family members described experiences with the health services where several actors have part responsibility for the treatment and follow-up of the heart failure patient. They found it challenging to move between the specialist health services and the municipal services. The meeting points in the specialist health services were the ward at admission and at specialist follow-up at the cardiac outpatient clinic. During admission to hospital they had to deal with a variety of medical personnel involved in the treatment on the ward. The contact network in the municipal services also involved several individuals: primary physician, rehabilitation units and employees in the home care services were mentioned. Some respondents said they experienced the communication between health personnel as inadequate, and that this constituted an extra burden. One family member put it like this: «It was impossible to relate to just one person, there were just too many of them (hospital doctors), and I didn’t feel I could bother them and ask too much there either. And when we came to the primary physician, he had to read through all the papers, he didn’t quite get it (the treatment)».

When the information did not quite add up, the family members were at a loss as to whom to trust, and several stated that they felt they were on their own. Episodes were described where the family member had to be the link between the specialists in the hospital and the primary physician. One respondent put it like this « … and I had to start explaining to the primary physician that they said this and that at the hospital and that he shall have such and such medication for so and so long». Another family member experienced being given the responsibility for coordination when she discovered a lapse in the information between the primary physician and the hospital doctors: «I do not want such great responsibility, I do not want to know more than them when he is ill. I just don’t want that.» Several respondents described it as a burden and a source of anxiety when health personnel did not agree on treatment: « … that worries me, for a cardiac specialist should know more than a general practitioner».

3) Available and competent supporters

Knowing whom to contact when they needed answers to questions or needed someone to share their worries with was important to family members. Several respondents described the heart failure outpatient clinic with follow-up and specialist competence as their most important support arena: «That they follow up, and that we do not have to nag to get an appointment». Several respondents said that knowing that they as family members could call if they needed to, made them feel appreciated, and made them feel more confident: «When I wonder about something, I have to call her (nurse). If I hadn’t met her, I don’t know, but she has been amazing … ». This availability was also described as being met with friendliness and attention.

Several respondents emphasised that a nurse at the heart failure outpatient clinic was an important contact person who helped them gain knowledge and understanding of the situation: «She explains so well, and she tells us what to do, and that is just wonderful. She does that every time we are there … and she tells us constantly why he is like that and what to watch out for, that has just been great.» The heart failure outpatient clinic was described as a hub where the nurse has a coordinating role and collaborates with other health service personnel from whom the patient receives services; such as home care nurses, primary physician and specialist. Some family members mentioned nurses in the home care services as well as important supporters: «Home care nursing is fabulous, we have met just the right people all the time, it is great». Several respondents described situations where the nurse had cleared up and set things straight when the information was inconsistent and had prescribed treatment. Competent nurses were greatly appreciated resources.

Discussion

The findings showed that family members have a need for relevant and precise information and qualified partners, included access to medical personnel with specialist competence. The family members we interviewed made it clear that it is difficult to be the resource that political intentions state they should be (12, 17). They wanted to know and understand more about what went on with their close ones suffering from heart failure in order to handle the situation better. Family caregivers need knowledge on the disease itself, the significance of symptoms, treatment and observations in order to develop the competence to manage the illness. Family members may experience an extra burden of anxiety and insecurity as a consequence of insufficient information on the illness. We make this clear in our first article (14).

Studies have documented that disease-related information and support to patients and their families contribute to better disease-management and lead to a reduction in the number of hospital admissions (9, 18). Involving family members when informing the patient has the potential advantage that two remember better than one, increasing the chances of proper adherence to the treatment (19). Heart failure can influence the memory and concentration of the patient (20, 21). Our findings show that family members have key tasks in the follow-up of the treatment and perform complex tasks to strengthen the patient’s ability for self-management of the illness. The family members we interviewed also said that their own need for information was related to being less worried for disease-related events. Prior studies show that being a family member of a heart failure patient is demanding (11, 14, 22-27). Other studies show that insufficient and ambiguous information in relation to an illness gives an increase in the feeling of insecurity (8).

Family members who are attentive to changes in the symptoms must be able to understand what to look for, and what the various signs mean (14). The absence of proper information to family members may be caused by a series of circumstances. Information to family members on the health condition of the patient and treatment depends on consent from the patient, if the situation demands it (28). The way patient confidentiality is interpreted and practiced by health personnel may be a factor in the involvement of family members.

Bøckmann and Kjellevold (29) point out that the way such regulations are practiced may constitute an obstacle more than the law itself, and that uncertainties around the limitations of patient confidentiality may restrict the amount of information given to family members. The Patients’ Rights Act (30) is clear on that next of kin shall receive information on the patient’s health condition and the help given, if the patient consents or conditions demand it. Norwegian studies show that information in hospital frequently is given to patients without any family members present, and that the patients have not been asked whether they want their family members present (11, 32, 33). There is evidently work to be done on how family members’ involvement can become an explicit and integrated part of the professional practice of health personnel.

It is well documented that outpatient clinics lead by nurses improve both survival and self-management behaviours in patients with heart failure (34,35). Specialist nurses in heart failure outpatient clinics offer consultations and coordination of services for patient and family members, and may be contacted by telephone. Health personnel who support and inform family members will be able to strengthen the family caregivers’ chance to be co-players for the ill person, and to manage their own situation (36). The majority of the family members we interviewed felt significant and included when they were able to take part in the follow-up of the heart failure patient. This finding corresponds with findings from other studies (26, 37).

An important finding in our study is that family members greatly appreciated health personnel that were available and possessed good medical knowledge. Several family members reported good experiences with effective and knowledgeable employees in the home care nursing services. These nurses had helped clear up ambiguous information, dealt with deteriorating health and avoided readmissions. This reflects the significance of high competence in the home care services as well, especially competence linked to identifying and acting when a patient’s conditions deteriorates. Studies show that the complexities of heart failure demand that nurses possess specialist competence in order to adequately inform and follow up patients with heart failure, and that there is a shortage of such competence (31, 35). A particular challenge in the municipal health services is a shortage of both specialist competence and continuity of the follow-up (38, 39).

The main goal of the collaboration reform is well-coordinated and unified health services (12). The reform entails a shifting of tasks from the specialist health services to the municipal health services. Family members interviewed by us experienced the presence of a multitude of health service employees involved in the situations of deterioration of the disease and treatment. They met nurses and doctors at various service levels and experienced it as unclear who was in charge at various times, although the primary physician is defined as the axis of the medical follow-up and treatment. The respondents said they felt they had been given a great responsibility for coordinating the services and this may indicate that the organisation of the health services appear fragmented.

The complexity of heart failure demands interdisciplinary follow-up and coordination, and this is clearly stated in the recommended guidelines for heart failure patients (40). Prior studies in other countries show that a lack of collaboration in the follow-up between service levels is a known problem (41). This also became clear from the PasOpp-report from 2013, a study of patient experiences with Norwegian hospitals. Forty per cent of the patients stated that the hospital did not collaborate satisfactorily with the primary physician on what was the cause of the patient’s hospital stay (42).

There is, in several countries, a shift toward nurses performing diagnosis-specific tasks in the municipal health services as well (43). We see this as an opportunity for letting nurses with specialist competence on heart failure work as a professional resource in teams with nurses in the municipality, making home visits at need and having consultations with patients and family members in a municipal cardiac outpatient clinic (44). Such an arrangement can also help increase the competence of nurses in charge of daily care of patients in the municipal health services, in the patients’ homes and in nursing homes. Continuous access to adequate medical competence in people who also know the patient and family caregivers may give faster reaction to subacute deterioration.

Studies show that nurses with specialist competence play a significant role in the quality of the health services and should be emphasised to a greater extent (45). The political signals given in 2015 (St.meld. 26), emphasising a holistic health service and an increase in competence (17), and the grant programme for master’s degree in advanced clinical nursing (46), are factors that may increase the quality of the services to patients and family caregivers.

Strengths and weaknesses

A strength of this study is the open approach; no questions to family members were decided in advance, as no Norwegian study has been published on the experiences of this group of informal caregivers. Another strength is that the initial analyses were performed by each individual researcher, and later collectively in the research group. The research group reached consensus on the results through discussion. The study’s sample has a large age span, a possible strength as more nuances of experiences were revealed. A limitation of the study is that the majority of participants were women, and that the majority was recruited through heart failure outpatient clinics with access to medical personnel with specialist competence. Information on the medical severity of the heart failure was not collected, and we have not uncovered whether the family members’ experiences change character with the degree of severity of the disease.

As the patients consented to their family members’ participation, we may have recruited family members in close touch with and well involved in the patient’s situation and in the collaboration with the health services. The study’s respondents were recruited by a nurse who knew the patient and the family, and we acknowledge the challenge to the volunteer aspect when recruiting is done through health personnel. The researchers made sure that the respondents were informed of their opportunity to withdraw from the study before, under and after the interview. Nobody chose to withdraw and several said it felt good to be able to talk about their experiences.

Conclusion

Family caregivers wish to understand any changes in the illness in order to support their close ones in the best possible way. In spite of family members’ experience of receiving insufficient information and an unclear services terrain, they also have positive experiences with available and competent nurses. The health services of the future have increased attention to family caregivers’ involvement and the expected increase in the number of patients with heart failure. In order to keep up with this development discussions on the responsibility to inform versus confidentiality and competence increasing efforts for nurses will be of significance for the quality of the services. Clearer communication between health service personnel will also be important so that the family caregivers may feel secure. In the municipal health services the emphasis on collaboration and competence development has the potential to give the heart failure patients and their family members good quality health services. There is a need for studies to examine the relationship between family members’ experiences, their assessments of the quality of the services and the competence of the nurses that follow up patients with heart failure in their homes.

References

1. Duerr A, Ellingsen CL, Egeland G, Tell G, Seliussen I, et al. Hjerte- og karregisteret. Rapport for 2012. Nasjonalt folkehelseinstitutt, Oslo. 2014.

2. Lindman A, Kristoffersen DT, Hassani S, Tomic O, Helgeland J. 30-dagers reinnleggelse av eldre 2011–2013. Resultater for sykehus og kommuner. Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter for helsetjenesten, Oslo. 2015.

3. Luttik ML, Jaarsma T, Lesman I, Sanderman R, Hagedoorn M. Quality of life in partners of people with congestive heart failure: gender and involvement in care. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2009;65(7):1442–51.

4. McMurray JJV, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Böhm M, Dickstein K, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. European heart journal. 2012;33(14):1787–847.

5. Piamjariyakul U, Smith CE, Werkowitch M, Elyachar A. Part I: Heart failure home management: patients, multidisciplinary health care professionals and family caregivers› perspectives. Applied Nursing Research. 2012;25(4):239–45.

6. Pressler SJ, Gradus-Pizlo I, Chubinski SD, Smith G, Wheeler S, Sloan R, et al. Family caregivers of patients with heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2013;28(5):417–28.

7. Pressler SJ, Gradus-Pizlo I, Chubinski SD, Smith G, Wheeler S, Wu J, et al. Family caregiver outcomes in heart failure. American Journal of Critical Care. 2009;18(2):149–59.

8. Kang X, Li Z, Nolan MT. Informal caregivers› experiences of caring for patients with chronic heart failure: systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2011;26(5):386–94.

9. Luttik ML, Jaarsma T, Moser D, Sanderman R, van Veldhuisen DJ. The importance and impact of social support on outcomes in patients with heart failure: an overview of the literature. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2005;20(3):162–9.

10. Luttik ML, Jaarsma T, Veeger N, van Veldhuisen DJ. Marital status, quality of life, and clinical outcome in patients with heart failure. Heart & Lung. 2006;35(1):3–8.

11. Hellesø R, Eines J, Fagermoen MS. The significance of informal caregivers in information management from the perspective of heart failure patients. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(3-4):495–503.

12. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. Samhandlingsreformen: Rett behandling – på rett sted – til rett tid. (St.meld. nr. 47 2008–2009). Departementenes servicesenter, Oslo. 2009.

13. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. Nasjonal helse- og omsorgsplan (2011–2015). (Meld. St. 16, 2010–2011). Departementenes servicesenter, Oslo. 2011.

14. Strøm A, Andersen KL, Korneliussen K, Fagermoen MS. Being «on the alert» and «a forced volunteer»: A qualitative study of the invisible care provided by the next-of-kin of patients with chronic heart failure. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2015;8:1–7.

15. Malterud K. Kvalitative metoder i medisinsk forskning. Universitetsforlaget, Oslo. 2011.

16. Giorgi A. Phenomenology and psychological research: Duquesne University Press. 1985.

17. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. Fremtidens primærhelsetjeneste – nærhet og helhet, (Meld. St. 26, 2014–2015). Departementenes servicesenter, Oslo. 2015.

18. Dunbar SB, Clark PC, Reilly CM, Gary RA, Smith A, McCarty F, et al. A trial of family partnership and education interventions in heart failure. Journal of Cardiac Failure 2013;19(12):829–41.

19. Dunbar SB, Clark PC, Deaton C, Smith AL, De AK, O›Brien MC. Family education and support interventions in heart failure: a pilot study. Nursing Research. 2005;54(3):158–66.

20. Pressler SJ, Subramanian U, Kareken D, Perkins SM, Gradus-Pizlo I, Sauvé MJ, et al. Cognitive deficits in chronic heart failure. Nursing Research. 2010;59(2):127–39.

21. Hawkins MAW, Schaefer JT, Gunstad J, Dolansky MA, Redle JD, Josephson R, et al. What is your patient›s cognitive profile? Three distinct subgroups of cognitive function in persons with heart failure. Applied Nursing Research. 2015;28(2):186–91.

22. Pihl E, Jacobsson A, Fridlund B, Strömberg A, Mårtensson J. Depression and health-related quality of life in elderly patients suffering from heart failure and their spouses: a comparative study. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2005;7(4):583–9.

23. Luttik ML, Jaarsma T, Veeger NJG, van Veldhuisen DJ. For better and for worse: quality of life impaired in HF patients as well as in their partners. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2005;4(1):11–4.

24. Saunders MM. Factors associated with caregiver burden in heart failure family caregivers. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2008;30(8):943–59.

25. Buck HG, Harkness K, Wion R, Carroll SL, Cosman T, Kaasalainen S, et al. Caregivers’ contributions to heart failure self-care: a systematic review. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2015;14(1):79–89.

26. Luttik ML, Blaauwbroek A, Dijker A, Jaarsma T. Living with heart failure: partner perspectives. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2007;22(2):131–7.

27. Makdessi A, Harkness K, Luttik ML, McKelvie RS. The Dutch Objective Burden Inventory: Validity and reliability in a Canadian population of caregivers for people with heart failure. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2011;10(4):234–40.

28. Lovdata. Lov om helsepersonell m.v. [helsepersonelloven]. Available from: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-64.

29. Bøckmann K, Kjellevold A. Pårørende i helse- og omsorgstjenesten. En klinisk og juridisk innføring. Fagbokforlaget; Bergen. 2015.

30. Lovdata. Lov om pasient- og brukerrettigheter [pasient- og brukerrettighetsloven]. Available from: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-63.

31. Hart PL, Spiva L, Kimble LP. Nurses› knowledge of heart failure education principles survey: a psychometric study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2011;20(21/22):3020–8.

32. Foss C, Hofoss D, Romøren TI, Bragstad LK, Kirkevold M. Eldres erfaringer med utskrivning fra sykehus. Sykepleien Forskning. 2012;7(4):324–33.

33. Bragstad LK, Kirkevold M, Hofoss D, Foss C. Informal caregivers› participation when older adults in Norway are discharged from the hospital. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2014;22(2):155–68.

34. Stromberg A. Nurse-led heart failure clinics improve survival and self-care behaviour in patients with heart failure. Results from a prospective, randomised trial. European Heart Journal. 2003;24(11):1014–23.

35. Lucas R, Riley JP, Mehta PA, Goodman H, Banya W, Mulligan K, et al. The effect of heart failure nurse consultations on heart failure patients› illness beliefs, mood and quality of life over a six-month period. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2015;24(1/2):256–65.

36. Löfvenmark C, Saboonchi F, Edner M, Billing E, Mattiasson A-C. Evaluation of an educational programme for family members of patients living with heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2013;22(1/2):115–26.

37. Liljeroos M, Ågren S, Jaarsma T, Strömberg A. Perceived caring needs in patient-partner dyads affected by heart failure: a qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2014;23(19/20):2928–38.

38. Gjevjon ER, Eika KH, Romøren TI, Landmark BF. Measuring interpersonal continuity in high-frequency home healthcare services. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2014;70(3): 553–63.

39. Potter T, Peden-McAlpine C. How expert home care nurses recognize early client status changes. Home Healthcare Nurse. 2002;20(1):43–50.

40. McDonagh TA, Blue L, Clark AL, Dahlström U, Ekman I, Lainscak M, et al. European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Association Standards for delivering heart failure care. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2011;13(3):235–41.

41. Jaarsma T, Brons M, Kraai I, Luttik ML, Stromberg A. Components of heart failure management in home care: a literature review. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2013;12(3):230–41.

42. Bjerkan AM, Holmboe O, Skudal KE. Pasienterfaringer med norske sykehus i 2013. Resultater på sykehusnivå: nasjonale resultater i 2013. PasOpp-rapport nr. 2 2014. Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter for helsetjenesten, Oslo. 2014.

43. Pulcini J, Jelic M, Gul R, Loke AY. An international survey on advanced practice nursing education, practice, and regulation. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2010;42(1):31–9.

44. Pattenden J. Heart failure specialist nurses: feeling the impact. British Journal of Primary Care Nursing: Cardiovascular Disease, Diabetes & Kidney Care. 2008;5(5):235–41.

45. Stewart S, Horowitz JD. Specialist Nurse Management Programmes: Economic Benefits in the Management of Heart Failure. PharmacoEconomics. 2003;21(4):225–40.

46. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. Proposisjon til Stortinget (forslag til stortingsvedtak) Prop. 1 (2014–2015). Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet; Oslo. 2014.

Comments