Palliative care during the end-of-life period in an intensive care unit - a quality assurance project

Background: The Norwegian Directorate of Health has issued national clinical guidelines for palliative care during the end-of-life period. Many dying patients in intensive care have a high symptom burden. To ensure that palliative care is of high quality, it is necessary to investigate whether clinical practice is in line with the applicable recommendations.

Objective: The objective was to examine documented practice of palliative care during the end-of-life period for patients in an intensive care unit. We also wanted to investigate whether practice was in accordance with the national clinical guidelines.

Method: The study is a quality assurance project with a retrospective review of patient medical records. We carried out descriptive, quantitative analyses. The sample consisted of adult patients over the age of 18 who died in an intensive care unit at a university hospital in Norway in 2021.

Results: A total of 88 patients died. Of these, 69 were included in the study. The median time between the withdrawal of life-sustaining interventions and death was twelve minutes. There was a documented nursing care plan for the withdrawal of interventions for 13% of the patients. There was no documented pain score for the patients who were conscious. Use of the Critical Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT) was documented for 16.7% of the patients who had a decreased level of consciousness, 58.3% of the comatose patients and 44.7% of the sedated patients. None of the patients who were conscious or comatose received a continual infusion of symptom relief medication, only bolus doses. Sedated patients received an infusion of opioids and/or sedatives. There were no documented conversations with the conscious patients. Conversations with patients’ families were documented by 94.2% of the doctors and 65.2% of the intensive care unit nurses.

Conclusion: The study shows that documentation of pain assessment and nursing care plans for dying patients in intensive care was inadequate. Documentation of information provided to patients was also inadequate.

Cite the article

Fjøsne K, Klepstad P, Gjeilo K. Palliative care during the end-of-life period in an intensive care unit - a quality assurance project. Sykepleien Forskning. 2023; 18(92261):e-92261. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2023.92261en

Introduction

The purpose of intensive care treatment is to maintain vital organ function in critically ill patients. Even though patients receive advanced intensive medical treatment, there are many who die (1). In 2021, 10.2% of patients in Norwegian intensive care units (ICUs) died, and this figure has changed little over the past five years (2).

Palliative care for patients during the end-of-life period in ICU is therefore a relevant area of competence. To ensure that patients’ needs for symptom management are met, ICU nurses must have knowledge and competence within palliative care (3).

International literature shows that ICU patients during the end-of-life period can suffer from many distressing symptoms, of which pain, anxiety and dyspnoea are the most common (1, 4, 5). However, symptom management is often inadequate (6). Implementation of nursing care plans and protocols for palliative care in ICU results in the increased use of pain relief and sedative medications and therefore a lower symptom burden (1, 7). Nevertheless, there is a lack of guidelines and nursing care plans for palliative care in ICU, and there is considerable variation as to whether these are used in clinical practice (5, 8).

In Norway, there are no national guidelines for palliative care in ICUs. However, the Norwegian Directorate of Health has issued national clinical guidelines for palliative care during the end-of-life period. The clinical guidelines are intended to help ensure that patients receive sound professional and evidence-based palliative care (9).

The national clinical guidelines indicate that different measures for managing, for example, pain, dyspnoea, anxiety and agitation should always be assessed. Suggested measures and the anticipated need of symptom relief medications should be documented in a nursing care plan, and regular assessments of the patient’s symptom burden must be carried out. In addition, communication with patients and their families must be ensured (9).

The national clinical guidelines provide general advice, and the Norwegian regional health authorities are responsible for ensuring that the guidelines are followed (9). The health service has a duty to carry out quality improvement work. It is necessary to examine whether clinical practice is in line with relevant recommendations (10, 11).

The objective of this study was to describe documented practice for pain assessment, medication-based symptom management, nursing care plans and communication with patients and their families during the end-of-life period in ICUs. We also wanted to investigate whether the practice is in accordance with the national clinical guidelines for palliative care during the end-of-life period. We used the following research question as a starting point:

‘What is the current documented practice of palliative care for patients during the end-of-life period in an ICU?’

Method

Design

The study’s design is a retrospective observational study (12) with a review of patient medical records in a time line from the withdrawal of life-sustaining interventions until the patient’s death. The study was also a quality assurance project at an ICU in which the objective was to summarise current documented practice. The results were intended to evaluate the quality of current practice (13).

Sample

The sample consisted of patients over the age of 18 who died in the main ICU at St. Olav’s University Hospital in 2021, regardless of the cause of admission. Life-sustaining interventions were withdrawn or a decision not to increase the level of treatment was made before death. Patients who were organ donors and patients who died during operations or despite active efforts to resuscitate them, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the case of cardiac arrest, were excluded from the study.

Data collection method

The data were collected from electronic anaesthesia and ICU records and electronic patient medical records. The variables that were used in data collection were based on the Norwegian Directorate of Health’s national clinical guidelines for palliative care during the end-of-life period (9). The variables were as follows: ‘age’, ‘gender’, ‘cause of admission’, ‘number of days between admission and death’, ‘time from withdrawal of interventions until death’, ‘consciousness at time of withdrawal of interventions’ and ‘respiratory support at time of withdrawal of interventions’.

In relation to pain assessment, we investigated whether there was documented use of the assessment tools Numeric Rating Scale 0–10 (NRS) or Critical Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT) (14). Local routines for pain assessment in the ICU indicate that if the patient is responsive, NRS is used. For patients who are unable to communicate, CPOT is registered regularly once per shift as well as when required, for example, when repositioning the patient.

We examined whether an individual nursing care plan had been documented. A nursing care plan contains measures for symptom management and a plan for the anticipated need for medication that might arise (9).

Furthermore, we examined which symptom relief medications the patient received for pain, gurgling in the lower respiratory tract, anxiety and agitation, as well as doses of medication before and after the withdrawal of interventions. The withdrawal of interventions is defined as the termination of life-sustaining treatment. The infusion speed of medication was registered 15 minutes prior to the withdrawal of interventions and immediately before the documented time of death.

In order to assess communication, we examined whether the provision of information regarding the course of the illness and prognosis to patients who were conscious had been documented. We also examined whether a conversation with the patient’s family had been documented by the ICU nurse and doctor, and whether the patient’s family was present at the time of withdrawal of interventions.

There were no recorded assessments of anxiety and agitation. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) is a tool for measuring the level of sedation, in which anxiety and agitation are factors (15). In the St Olav’s University Hospital ICU, this is used solely to measure the depth of sedation.

The patients were categorised in four groups, based on their documented level of consciousness: 1) sedated patients, 2) comatose non-sedated patients, 3) patients with a decreased level of consciousness, and 4) conscious patients.

Before commencing data collection, we pilot tested variables (12) on four patients. A data review was conducted by the first author in February–March 2022. Cases in which there was doubt concerning the categorisation of data and the extent to which treatment followed the guidelines were discussed individually with the second author.

Data analysis

We carried out descriptive analyses using the analysis software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 27 (16). Descriptive analysis is used to describe and summarise the data. Categoric variables are presented as absolute numbers (n) and percentages (%).

Continuous variables are presented with central tendencies and dispersion. Normally distributed data are presented as averages and standard deviations (SD), and non-normally distributed data with median and interquartile range (IQR) (12).

Ethical considerations

This project was a retrospective study and did not alter or affect patient treatment. The project was an internal quality assurance project that was outside the mandate of the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK), and did not come under the substantive scope of the Health Research Act, see sections 2 and 4.

The project was carried out with support from hospital management in accordance with the requirements for quality assurance in the Health Personnel Act, see section 26 (17). The head of the project filled in a self-assessment form in conjunction with the Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA). The hospital’s research committee assessed and approved the project in line with the hospital’s routines for quality assurance projects and the protection of personal data. We followed the hospital’s routines for safe storage in a dedicated file area.

Results

Description of sample

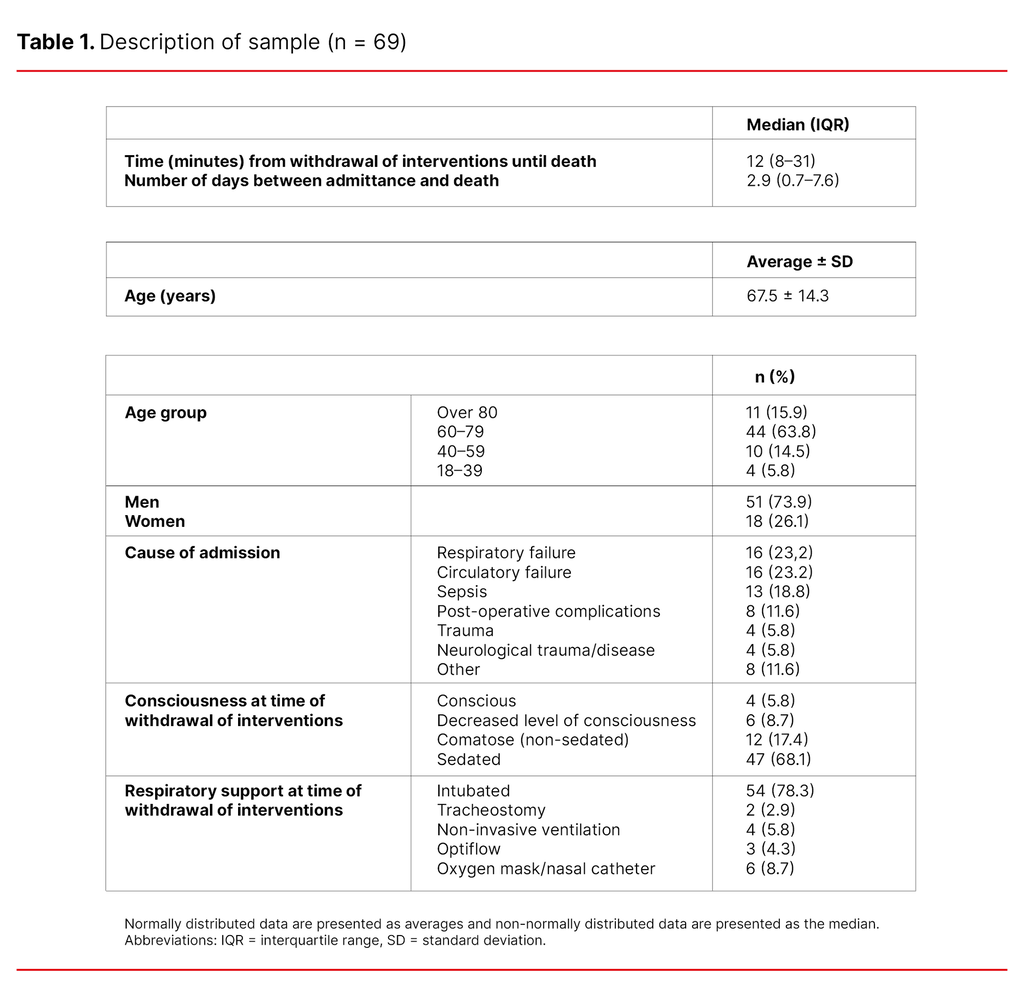

A total of 88 patients died. Of those, we excluded eleven patients who were organ donors and eight patients who died during operations or after active efforts to resuscitate them. We analysed the medical records of 69 patients. The majority of the patients were men (73.9%), and the most frequent causes of admission were respiratory failure (23.2%) and circulatory failure (23.2%) (Table 1).

As shown in Table 1, the median time from withdrawal of interventions until death was 12 minutes and the number of days between admission and death was 2.9 (median). Most of the patients were over 60 years of age (79.7%) and only four of the patients were under the age of 39 (5.8%). A majority of the patients were sedated (68.1%).

Nursing care plans and symptom assessment

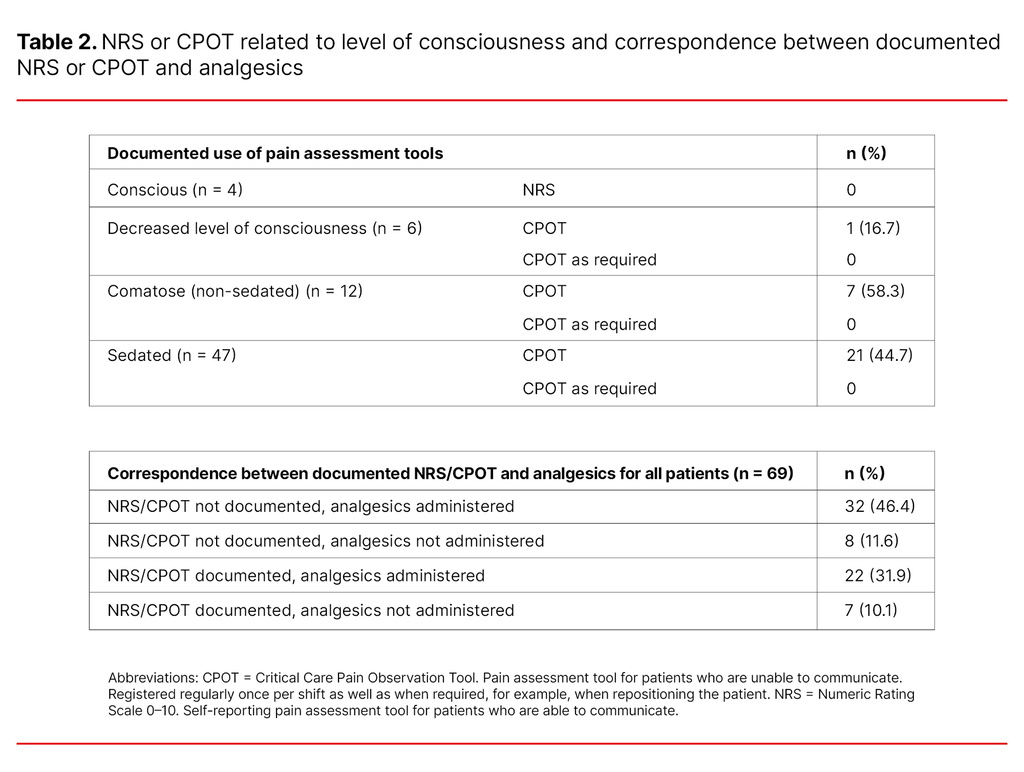

There was a written nursing care plan for the withdrawal of life-sustaining interventions for 13% of the patients (n = 69). Pain rated from 0–10 using the self-reporting assessment tool NRS was not documented in the case of the four conscious patients.

Pain assessment using CPOT for patients with a reduced ability to communicate was documented in 16.7% of the patients who had a decreased level of consciousness, in 58.3% of the comatose patients and in 44.7% of the sedated patients.

The use of CPOT as required was not documented in relation to any of the patients. Analgesics were administered to patients without documented pain assessment as frequently as to patients with documented pain assessment (Table 2).

Symptom relief medications

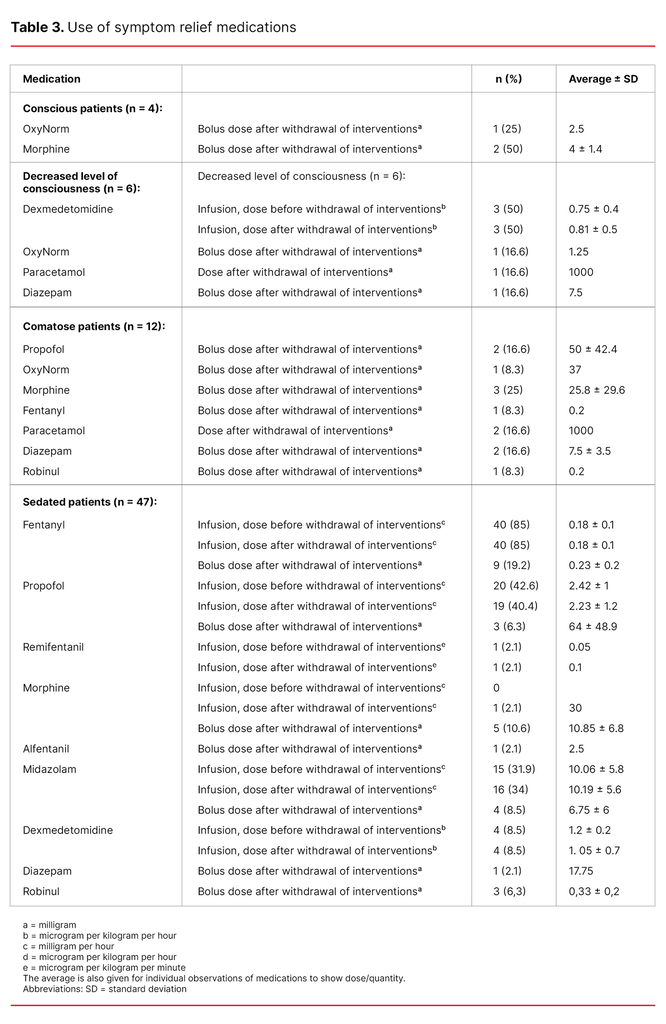

None of the conscious patients received a continual infusion of symptom relief medications, but three of the four conscious patients received bolus doses of opioids (Table 3).

As shown in Table 3, one of the patients who had a decreased level of consciousness was given opioids, one was given paracetamol and one patient was given diazepam after the withdrawal of interventions. None of the comatose patients received continual infusions with symptom relief medications (Table 3).

Table 3 shows that sedated patients (n = 47) received an infusion of opioids and/or sedatives. The dose before and after the withdrawal of life-sustaining interventions was approximately the same, except in the case of one patient who only received remifentanil and another who received an infusion of morphine in addition to other analgesics. Roughly a quarter and a tenth of the sedated patients were given bolus doses of analgesics and sedatives, respectively, after the withdrawal of life-sustaining interventions.

Communication with patients and their families

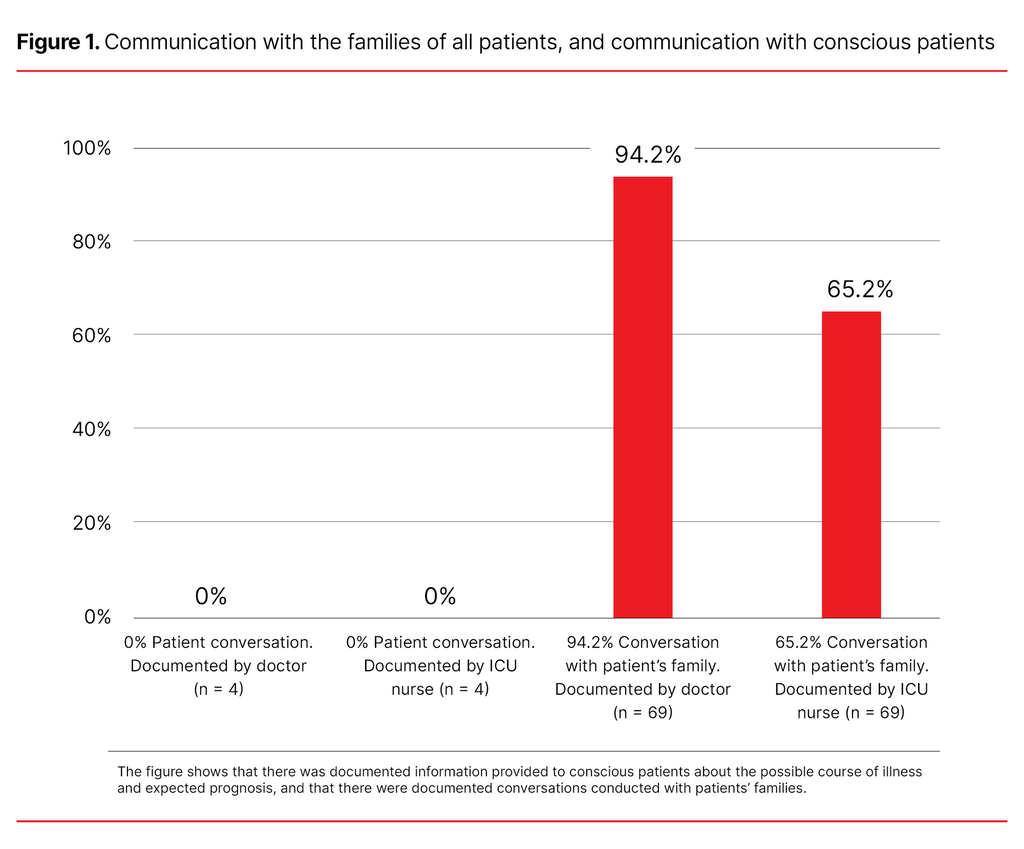

No conversations with the conscious patients were documented by nurses or doctors. In relation to all of the patients, conversations with their families were documented by doctors in 94.2% of cases and by ICU nurses in 65.2% of cases (Figure 1). The majority of patients had family members present when interventions were withdrawn (74%).

Discussion

The study showed that there was inadequate documentation of pain assessment and nursing care plans. For conscious ICU patients there was, in addition, inadequate documentation of information provided when life-sustaining interventions were withdrawn.

Pain assessment

In this study, pain assessment was not documented for any of the conscious patients and only for about half of the unconscious patients. In the national clinical guidelines (9), regular observation of the patient’s clinical condition is recommended to achieve good symptom management.

Moreover, the local guidelines for pain assessment in the ICU stipulate that patients are to be assessed using NRS or CPOT once per shift and otherwise as required. The results are consistent with the findings from other studies (18, 19), which show that a low percentage of ICU patients have documented pain assessment.

The findings are surprising since carrying out systematic symptom assessments using validated tools is a prerequisite for good quality management of distressing symptoms in dying patients, for both conscious and sedated patients (14, 20). This study did not examine the reasons why pain assessment was poorly documented. One possible reason may be that the ICU nurse had asked the patient without documenting the response, or that the ICU nurse had perceived the patient as being so deeply sedated or comatose that they thought it was unnecessary to assess them using CPOT.

The results show, however, that analgesics were administered to patients without documented pain assessment as frequently as to patients with documented pain assessment. Regardless, ICU nurses should document the assessments they make (17), and the possibility cannot be ruled out that patients have experienced pain that has been overlooked due to a lack of systematic assessment and documentation.

Nursing care plans

In our study, only 13% of the patients had a documented nursing care plan. The national clinical guidelines stipulate that a nursing care plan for the withdrawal of life-sustaining interventions as well as anticipated needs for medication should be documented in patients’ medical records. Earlier studies (21, 22) have shown that ICU nurses prefer a written nursing care plan in order to provide the best possible end-of-life care for patients.

One study (23) found that nurses regarded a nursing care plan as a useful tool. Another study (24) found that a lack of clear guidelines for the withdrawal of life-sustaining interventions resulted in ICU nurses being uncertain as to what were the correct interventions after withdrawal. One possible problem with using nursing care plans was that standardised plans were a barrier to individualised patient care.

A possible explanation as to why only nine of the patients had a documented nursing care plan was that ICU nurses can notify doctors when symptoms arise, and interventions and medications can then be administered on an ongoing basis. This is possible in ICUs where a doctor is present at all times. It is also likely that the doctor and the ICU nurse in many cases discussed a plan without registering this in the patient’s medical records. In addition, the necessity of a nursing care plan is debatable when the median time from the withdrawal of interventions until death is 12 minutes.

A Dutch observational study (27), in which the median time from withdrawal of interventions until death was 20 minutes, concluded however that a new guideline with advice on prevention of distressing symptoms was effective, and that most of the patients had a low symptom burden. If this is the case, nursing care plans will be of use even though there is only a short period of time between the withdrawal of interventions and death.

Medication-based management of distressing symptoms

The results of our study showed that there was no increase in medication doses before and after withdrawal of interventions in sedated patients, apart from two patients who were given morphine and remifentanil respectively in addition. This finding contrasts with several other studies that found that doses of opioids were increased when life-sustaining interventions for ICU patients were withdrawn (27−29).

There are several possible explanations for this variation. A guideline or individual nursing plan for the withdrawal of life-sustaining interventions can make it easier for ICU nurses to increase doses of analgesics and sedatives. This correlates with the findings of the Dutch observational study (27), which found that when a new national protocol for end-of-life care was introduced, the use of midazolam, propofol and opioids increased significantly.

Furthermore, the patients in our study may have been more heavily sedated to begin with than those in the other studies, such that it was not necessary to increase the medication dose. We did not collect data on depth of sedation, so we cannot compare the level of sedation in the course of care. In addition, the time from withdrawal of interventions until death was 12 minutes in our study.

Experience suggests that with such short time intervals, the choice is often made to administer bolus doses based on need, which a number of the patients in our study received. When the median time is only 12 minutes, it may indicate that the patients’ conditions are so critical that they are already in the advanced stages of dying when interventions are withdrawn and do not, therefore, have a greater need for palliative medications. However, in the studies from the Netherlands (27) and the United States (28), in which the median time interval from withdrawal of interventions until death was 20 minutes and 42 minutes respectively, there was a substantial increase in medication doses.

Less than half of the comatose patients were given analgesics, and a sixth received medications for anxiety and agitation. This finding corresponds to the US study (28), which showed that comatose patients were given less morphine than other patients. It may be that analgesics are not administered to comatose patients who do not respond to pain stimuli because it is assumed that they do not feel pain.

The experience of pain is subjective (30), and when there is no reaction to pain stimuli it is likely that there is little need for analgesics. Therefore, it is not surprising that comatose patients are given lower doses than other patients. For neurocritically ill patients with a minimum level of consciousness who may experience pain that they are unable to communicate, it is, on the other hand, important that ICU nurses observe signs of discomfort and administer sufficient levels of analgesics (30, 31).

An interesting finding was that patients with a decreased level of consciousness and conscious patients only received bolus doses of symptom relief medications, and the doses administered were low. Only one patient received non-opioid analgesics. It is therefore difficult to compare with other studies in which patients received continual infusions of medication (27, 28).

It may be assumed that in the case of extreme deterioration of conscious patients, it was more practical to administer analgesics based on need. In addition, there was a lack of documented pain assessment using NRS and CPOT, which makes it difficult to know the actual symptom burden and need for palliative medications. Experience indicates that some ICU nurses and doctors can be reluctant to give opioids to dying patients for fear of adverse effects such as respiratory depression and hypotension. There is little evidence to support this practice, since a number of studies show that the increased use of opioids can extend the time from withdrawal of interventions until death (27−29).

Communication with patients and their families

A total of 94.2% of patients’ families had had conversations with the doctor, which is a high level compared with a study from the United States (32), which found that interdisciplinary meetings with patients’ families were documented in less than 20% of cases. Conversations with patients’ families is important, since the time between critical illness and death is short in an ICU.

One study (33) showed that clear and honest communication was a factor that affected the satisfaction of patients’ families when the patient was in the end-of-life period, and it helped to prevent post-traumatic stress among family members. The national clinical guidelines (9) stipulate that healthcare personnel are to ensure that the needs of patients and their families for conversations and information during the end-of-life period are met, but our study only examined whether conversations were documented. We did not examine the content of the information that was provided, nor whether patients’ families felt that they had received sufficient information.

No conversations in which patients were given information about the possible course of illness and expected prognosis were documented by ICU nurses or doctors with the four conscious patients. This is an interesting finding because patients have a right to information regarding the condition of their health (34).

Our study only examined the documented practice. It is to be hoped that conversations were carried out with patients without this being documented in their medical records. Nevertheless, it is unfortunate that there was no documentation of the information provided to patients, or in relation to whether the situation made it impossible to provide information.

The patient must be given continuous updates on their condition and, if possible, participate in decision-making processes in conjunction with the withdrawal of life-sustaining interventions (9). If not, this may result in a failure to clarify the patient’s wishes, such as the need for religious rituals or ideas about how the withdrawal should be carried out, or that the patient lacks assurance that pain and discomfort will be relieved.

In our study, only four of the patients were categorised as conscious, so we are unable to conclude this with any certainty. Nevertheless, the finding indicates that the practice of providing information to conscious patients who are critically ill in ICUs must be studied further.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

One weakness of the study is that it was retrospective and only examined documented practices, which means that assessments and interventions may have been carried out that were not documented. Another weakness was that the patients who did not die in the ICU after the withdrawal of interventions but were transferred to a ward were not included. Information about what palliative care they received prior to being transferred would have been relevant to the study.

It is also a weakness that the sample only came from one ICU, which limits generalisation. The results do not necessarily represent other ICUs, which may have their own internal guidelines and routines.

A significant strength of the retrospective design is that we avoided bias, in that none of the nurses or doctors in the ICU knew that the data were going to be used for this purpose. Therefore, they could not influence the results (12).

Conclusion

The study shows that there was inadequate documentation of pain assessment, nursing care plans and information provided to dying ICU patients, if documented practice is to be in accordance with the national clinical guidelines for palliative care during the end-of-life period.

A particularly important finding was that there was no documentation of information to any of the conscious patients. The findings in the study highlight that it is important to be aware of palliative care for ICU patients, to ensure good routines for pain assessment and for planning end-of-life symptom management.

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0.

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Most read

Doctorates

Selvrealisering og betydning for helsesykepleieres fortsatte yrkesutøvelse. En kvalitativ studie.

Dårlig samvittighet hos sykepleiere - En multimetodestudie om sykepleieres erfaring med dårlig samvittighet i sykehjem og hjemmebasert omsorg

Helserelatert livskvalitet og mental helse etter ekstremt prematur fødsel

Å leke med dukker i sykepleierutdanningen

Comments