COVID-19: Contact with a school nurse during the first lockdown – a cross-sectional study

Few of the pupils had been informed that they could contact the school nurse during the school closure or had used the online chat service or helpline.

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic in Norway has had a major impact on adolescents. Schools were closed and stringent restrictions were imposed. The adolescents reported reduced satisfaction with life and indicated that they felt lonely and not as happy. The school closures happened in tandem with changes to school health services. A number of school nurses were reassigned to other tasks, which reduced the service for adolescents.

Objective: The main aim of this study was to look at how young adolescents’ concerns and challenges during the first lockdown impacted on the uptake of the school nurse service. We also compared boys’ and girls’ contact with a school nurse, and looked at whether they had received information on how to get in touch with a school nurse during the school closure.

Method: The cross-sectional study was conducted in the counties of Innlandet and Viken in May 2020, and data were collected via online questionnaires. A total of 3347 adolescents from Years 8–10 participated. Descriptive analyses and logistic regression analysis were performed.

Results: More adolescents experienced a positive effect (74.9%) from the pandemic than a negative effect (68%). Among the girls, 49.5% were worried about being infected with COVID-19, while this applied to just 30% of the boys. Less than half of the adolescents contacted a helpline or used an online chat service, and more girls than boys considered doing so. Forty-one per cent had received information on how to contact a school nurse during the school closure, and 36% had not. The logistic regression analysis showed that girls were more likely than boys to contact a school nurse during the first lockdown.

Conclusion: The study shows that the first lockdown had both a positive and negative impact on adolescents. Few of the pupils had been informed that they could contact a school nurse during the school closure. In such situations, it is important that clear information is provided on how school nurses can be reached, and that they are available to the adolescents.

The COVID-19 pandemic hit Norway in March 2020, and on the 13th of that month, all schools were closed, and would remain so for almost two months. Restrictions were introduced that impacted on the daily lives of adolescents and curtailed their leisure activities and social contact with friends and others. The health authorities advised the population to limit the number of close contacts and to practise social distancing indoors (1). These measures dramatically changed how adolescents lived their lives.

During the pandemic, adolescents reported reduced satisfaction with life (2). During the same period, one in five children and adolescents in Years 3–10 in Denmark reported that they felt lonely. Just under half reported that they were not happy (3). Loneliness and social isolation among children and adolescents can be a risk factor for mental health problems (4).

Physical presence at school is important for adolescents who struggle with their mental health. The school closures meant that adolescents lost this constant in their lives (5). Adolescents who met up with friends in person during the pandemic reported fewer symptoms of mental health problems, and they were less lonely (6).

One study indicates that having contact with fewer friends during lockdown was not associated with a poorer quality of life. However, the same study also shows that adolescents who were in quarantine or self-isolation reported that their quality of life was negatively affected (7). Imposed isolation was associated with mental health problems among the adolescents, such as depression and anxiety, and these issues worsened the longer the period of isolation (4).

School closures and stringent infection control measures led to changes in everyday life. A number of the adolescents had challenges and concerns in relation to the pandemic. They mainly shared these concerns with family and friends, but also with teachers and healthcare personnel (8). School nurses can be a natural point of contact for adolescents to share their concerns (9).

School health services are a low-threshold service that should be easily accessible for all pupils. In many schools, these services solely consist of a school nurse. The school health services were the first service that adolescents could contact for help with health-related issues on their own initiative. The aim is to promote physical and mental health, ensure good social and environmental conditions and prevent illness and injury (10).

Adolescents contact school health services for various reasons, for example to seek help with a physical injury or illness, mental health issues, bullying and conflicts with their parents (11). Girls contact school health services more often than boys (11, 12). Before the pandemic, the 2019 Ungdata survey showed that 39% of lower secondary school pupils contacted a school nurse (13).

When the schools were closed, changes were also made to the school health services. Many school nurses were reassigned to contact tracing duties, which reduced the capacity in school health services and consequently the access for adolescents. Several school health services and health centres for adolescents were closed during this period (14).

We know that the COVID-19 pandemic has had an impact on adolescents and has changed their daily lives, particularly during the school closures (2, 3). However, little is known about their contact with school nurses during a pandemic.

We therefore wanted to examine adolescents’ concerns and challenges during the first lockdown as well as the likelihood of them contacting a school nurse. We also compared the amount of contact boys and girls had with a school nurse respectively, and looked at whether they had received information on how to get in touch with a school nurse during the school closure.

Method

Design and setting

We analysed data from the online cross-sectional survey on the experiences of lower secondary school pupils in the counties of Innlandet and Viken during the pandemic (Ungdom i koronatiden i Innlandet og Viken). The survey was conducted in the period 6–31 May 2020 under the auspices of the regional competence centre for addiction issues (KORUS Øst), which covers 79 municipalities in Innlandet and Viken (15).

Questionnaire

The questionnaire is an adapted version of the questionnaire by the Norwegian Social Research Institute (NOVA) aimed at Oslo adolescents during the pandemic (Oslo-ungdom i koronatiden) (16). The questionnaire was largely based on the Ungdata survey (17), in which school pupils across the country answer questions about their well-being and how they spend their leisure time.

The questionnaire was supplemented with questions from KORUS-Øst on how the pandemic had impacted on adolescents’ lives, their well-being, their contact with friends and family, how they spent their leisure time, and how well home schooling worked. As KORUS-Øst is the national body for identifying and recording problematic gaming, questions were included about computer gaming, the use of social media, screen time and gambling.

The online survey consisted of 52 questions in total, and none of the questions were considered to be sensitive enough to warrant special approval. The questions were formulated in a way that could apply to both home schooling and to work in school when the schools gradually started to reopen.

All questions in the questionnaire were multiple choice. KORUS-Øst collected data via Questback. The survey took about 20 minutes to complete, and participation was voluntary.

Sample and recruitment

The study was aimed at all lower secondary school pupils in Years 8–10, which covered approximately 11 950 adolescents in KORUS-Øst’s catchment area. Participation was voluntary for the local authorities. KORUS-Øst emailed information about the survey to its contacts in the local authorities, who were mostly SLT (coordinated local initiatives for substance use and crime prevention) personnel, coordinators, heads of education and educational advisers. The contacts received a follow-up phone call a few days later.

The 33 local authorities that wanted to participate were sent a link to the survey. The contacts were responsible for sending the link to headteachers, who in turn forwarded them to the teachers. The adolescents and their parents/guardians received information about the study from a teacher. Responses from 3 347 adolescents were included in the study.

Variables

Concerns and challenges during the first lockdown

In order to measure challenges and concerns in relation to the pandemic, we asked how worried they were about getting sick with COVID-19, about friends or family getting sick with COVID-19, and about infecting others with COVID-19. The response alternatives were on a scale from 1 (‘Not worried at all’) to 4 (‘Very worried’).

Based on the analysis, the variables were dichotomised to ‘Not worried’ versus ‘A little, fairly and very worried’. The adolescents were also asked whether there had been more or less family conflicts since the start of the pandemic, with five response alternatives from ‘Much fewer than before’ to ‘Much more than before’, and whether any of their parents/guardians had lost their job or been laid off.

They were also asked questions about whether the pandemic has had a negative or positive impact on their lives respectively. The response alternatives were on a scale from 1 (‘Yes, very much’) to 5 (‘No, not at all’). The variables were dichotomised to yes (‘Yes, very much’, ‘Yes, somewhat’, ‘Yes, a bit’) and no (‘No, not at all’).

Use of support services during first lockdown

The adolescents were asked if they had contacted the school nurse during the school closure, and if they had contacted a helpline or used an online chat service, with the response alternatives ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘No, but have considered it’.

They were also asked if they had received information on how to contact the school nurse, with the response alternatives ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘Don’t remember/No, but have considered it’. Based on the logistic regression, this variable was dichotomised to yes (‘Yes’) and no (‘No’, ‘Don’t know/Don’t remember’).

Analysis

We analysed the data material using IBM SPSS Statistics 26. All variables were analysed descriptively, and we used cross-correlation in a chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test respectively to test for gender differences.

We then conducted both univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses for ‘Contact with the school nurse’ as a dependent variable, and each of the following as independent variables: gender, family conflicts, various concerns, and information about school health services. Categorical variables were coded as dummy variables.

Ethics

The survey was anonymised, and it was not possible to identify individual responses or survey participants. We used the Questback tool in anonymous mode, which meant that respondents’ IP addresses could not be traced. All data protection requirements were fully complied with. The adolescents decided themselves whether they wanted to participate, but parents/guardians of children under the age of 18 had the right to deny participation. Parents/guardians who did not want their child to participate had to ask them to refrain from participating, or they could contact the class teacher.

Adolescents who wished to talk about the survey after completion could contact a trusted adult or the support services. No personal information was collected. In order to maintain anonymity, we only asked for gender and municipality. The data protection officer at Innlandet Hospital Trust deemed the data in the project to be anonymous, and therefore not subject to data protection legislation (ref. number 14156583).

Results

Table 1 shows that 74.9% of the adolescents stated that the pandemic had had a positive impact on their lives, while 68% stated that it had had a negative impact. Both questions could be answered.

Approximately 16% more girls than boys reported a negative impact. Half of the girls were worried about being infected with COVID-19, compared to just 30% of the boys. The majority of both boys and girls (89.3%) were worried about infecting others.

Among the girls, 83.9% were worried about infecting others, compared to 62.3% of the boys. One in five (20%) adolescents indicated that one or both parents had been laid off or lost their job due to factors related to the pandemic, and these were more or less evenly distributed between the sexes.

Fifty-one per cent thought that there was little or no change in the number of family conflicts during the school closure compared to before the pandemic. More girls (27.6%) than boys (22.3%) reported an increase in family conflicts during lockdown.

When asked whether they had contacted a helpline or used an online chat service in the last month of the school closure, 2.8% answered that they had, and 5.3% indicated that they had considered it. Significantly more girls than boys had considered it.

When asked if they had been in contact with a school nurse in the last month of the first lockdown, 6.7% answered ‘Yes’, while 3.2% had only considered it. Twice as many girls as boys answered ‘Yes’ to this question.

In answer to the question on whether they had received information on how to get in touch with a school nurse, 41.5% indicated that they had, 36.3% responded ‘No’, and 22.2% answered ‘Don’t know/Don’t remember’. Table 2 shows the use of support services, distributed by gender.

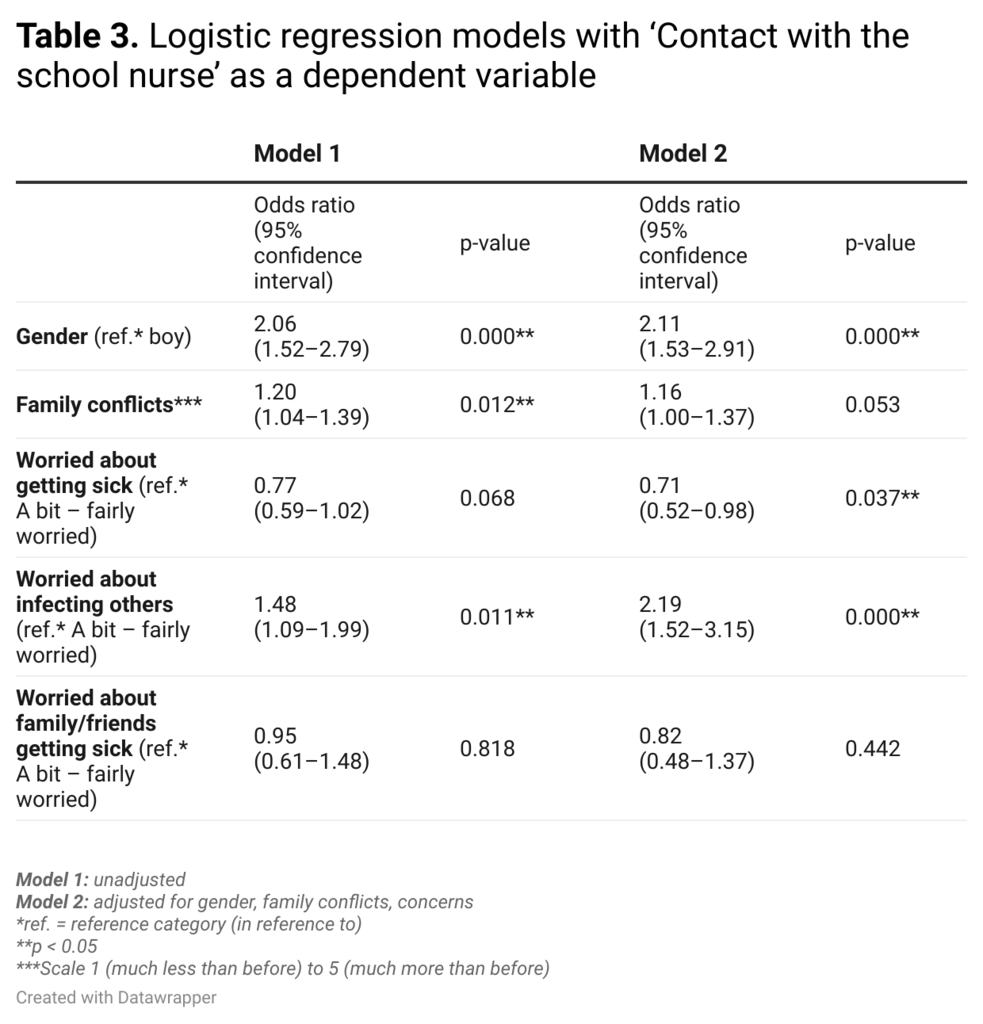

The unadjusted logistic regression model (Table 3, model 1) confirms the descriptive analyses: girls were more likely to contact the school nurse than boys (odds ratio [OR] = 2.06, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.52–2.79). The rise in the number of family conflicts during the first lockdown was associated with higher odds of contacting the school nurse (OR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.04–1.39).

When we compared adolescents who had been a bit or fairly worried about infecting others and those who had not been worried about this, the latter had higher odds of contacting a school nurse during the first lockdown (OR = 1.48, 95% CI: 1.09–1.99). The adjusted model (Table 3, model 2) shows higher odds for girls contacting a school nurse.

Adolescents who were not worried about infecting others had higher odds of contacting the school nurse, while the odds for family conflicts were lower, but not statistically significant. The table shows little change in the odds ratios when comparing single and multiple analyses, where variables such as gender, concerns and family conflicts were integrated.

Discussion

How did the pandemic impact on the adolescents?

The adolescents in this study reported that the pandemic had impacted on their lives. A number of them felt that lockdown had had a positive impact on their lives. One explanation for this may be that they enjoyed spending more time with their family. This finding is consistent with a study of adolescents in Oslo, who indicated that the pandemic had had a positive effect as they had more free time and were able to do more with their family (16).

A number of adolescents felt that lockdown had had a positive impact on their lives.

An international study found that adolescents had more time for enjoyable activities during the pandemic. They spent more time on their computers, their days were less hectic during the school closures, they relaxed more and slept better (18).

Another study shows that adolescents had more peace to do their schoolwork and were able to concentrate better. In addition to trying to do well at school, adolescents are often busy with leisure activities and friends, so they welcomed the break and the opportunity to concentrate on schoolwork. The same study also shows that during school closures, everyday life improved for adolescents who struggle socially or have anxiety (19).

One-fifth of the adolescents reported that one or both parents had been laid off or lost their job. Combined with the recommendation or order to work from home, this meant that many adults spent more time at home during the school closure.

Our results further show that half of the adolescents did not report more family conflicts than usual, which may have been part of the reason why the pandemic did not unequivocally have a negative or positive impact on their lives. However, a proportion of the adolescents reported the first lockdown as a negative experience; more so girls than boys. Lockdowns can affect adolescents’ quality of life. This disparity between the sexes is consistent with a previous study that reported that gender is a factor in quality of life, with girls reporting a generally poorer quality of life than boys (20).

During lockdown, several stringent restrictions were introduced, including in relation to contact with other people, which led to some adolescents feeling lonely (3). Not all adolescents live in stable family relationships where the family constitutes a safe base. Earlier studies show that adolescents who experience violence or other problems in the home had a difficult time during the school closures (21), when they spent more time with their family than usual. It may be reasonable to assume that these adolescents reported that the lockdown had a negative effect.

In our study, a significantly higher proportion of girls than boys reported a rise in family conflicts, which can be regarded as a negative experience. This finding is consistent with previous studies, which show that more girls than boys report family conflicts (12).

The rise in family conflicts could be due to several factors. Having to spend more time together in a confined space can lead to clashes. Several international studies reported an increase in family conflicts and that this was related to stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic (18, 22).

Concerns about COVID-19

The study showed that adolescents were worried about being infected with COVID-19, and the proportion was significantly higher for girls than boys. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that girls generally worry more than boys (12, 23). The fact that girls worry more than boys may be due to girls being more sensitive to stress, which in turn can lead to increased concern (23), and the pandemic can be a source of stress for adolescents.

The proportion was significantly higher for girls than boys.

The school nurse is someone with whom the adolescents can talk about their concerns. Both prevention of and information about infectious diseases and infection control are important areas of competence for school nurses. This competence is important when dealing with adolescents who are worried about being infected or infecting others. School health services are subject to the legislation on protection against infectious diseases (10).

According to the Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, the school nurse serves as the school’s resource for infection control competence (24). This competence meant that the school nurses were reassigned to other tasks, such as contact tracing or working on the COVID-19 helpline during the first lockdown (25).

A survey of 45 school health services showed that 64% of these had reduced capacity during the first lockdown, and that between 30% and 70% of all consultations or appointments were cancelled (14). Reassigning school nurses and reducing the availability of services for adolescents could be interpreted as a signal that adolescents are not a prioritised group.

Use of support services

In this survey, the adolescents were asked if they had contacted or had considered contacting a helpline or using an online chat service. Few had made contact, but several had considered it – significantly more girls than boys. The low uptake may be because the survey was conducted at an early stage in the pandemic, when there was perhaps less need for a helpline or chat service.

The survey was conducted in May 2020, at which point the Government was starting to ease the stringent restrictions and some lower secondary schools were able to reopen. Another contributing factor may be that adolescents were reluctant to use a helpline in case their parents overheard their conversation (26).

However, the first lockdown represented a phase of the pandemic that was characterised by a great deal of uncertainty and concern, and it could be assumed that the adolescents needed to talk to someone and contact the support services.

Over 90% of the adolescents did not contact the school nurse during the first lockdown.

Our survey shows that over 90% of the adolescents did not contact the school nurse during the first lockdown. This may quite simply be because they did not have a need to use the service at that time. Another reason may be that they were unaware that they could contact the school nurse during the school closure. Many school nurses do not work in the school every day, some work at several different schools, while others work part time (27). This could also be part of the reason why few adolescents contacted a school nurse.

The analyses showed that half of the adolescents had not received or did not remember if they had received information about how they could get in touch with a school nurse. This finding is consistent with the study by Hafstad and Augusti, which shows that only one in three adolescents stated that they had been told how to contact the school nurse during the first lockdown (28).

In times of crisis, such as a pandemic, it may be that adolescents are not as receptive to information about contacting the school health services. Adolescents were having to absorb the enormous amount of information that was being issued about the pandemic, and the method of dissemination is important here. A study shows that TV and family were the most common sources of information for adolescents learning about the pandemic, while Snapchat and Facebook were the most used social platforms (7).

If a school nurse posts information on one of these platforms, it can be assumed that adolescents are more likely to see it. Another reason may be that the adolescents were given no information or poor information, and that it was unclear how the service would work during lockdown.

Regression analyses show that the girls were more likely to contact a school nurse during the pandemic, and this tendency is also seen in earlier studies (12, 29). This may be because girls are better at voicing their concerns and more open to discussing their problems with others. Adolescents contact school nurses for a variety of reasons, and many do so on impulse.

It is crucial that school health services are accessible, and this can impact on adolescents’ uptake of the service. Studies have shown the importance of school nurses being available for adolescents and keeping an open door for them (30). Adolescents have previously indicated that they would like the school nurse to be present every day and to have drop-in appointments (31).

The low uptake of the school nurse service among adolescents who were worried about infecting others was a surprising and unexpected result.

When this survey was conducted, many school health services were closed, and the school nurses’ availability and visibility were reduced. This may be part of the reason why 87.2% of the girls and 94% of the boys did not contact a school nurse during the first lockdown.

The low uptake of the school nurse service among adolescents who were worried about infecting others was a surprising and unexpected result. The same applies to other concerns related to the pandemic that were not statistically significant in terms of the contact with school nurses.

These interpretations have some statistical limitations since the majority of adolescents did not contact a school nurse during the first lockdown. One possible explanation may be that the adolescents were not generally aware that they could contact a school nurse when they are worried or experiencing problems.

Another explanation may be that the school nurse was not very visible at school. Visibility and accessibility are important for the adolescents to be able to make contact. The visibility of school nurses varies from school to school, and also depends on the individual nurse (12, 27).

A previous study shows that adolescents want school nurses to be more visible; they want them to have a greater presence during classes and breaks, and to have an accessible office (31). Adolescents who did not know how to get in touch with a school nurse before the pandemic were probably less likely to make contact during a pandemic, especially when the schools were closed.

Methodology considerations

The survey was sent to all local authorities in the county of Innlandet and parts of Viken, and several local authorities did not participate. The teachers sent the survey link to the pupils, and it was not possible to ascertain whether the adolescents responded when they were studying at home or in their free time. In the case of the latter, this could reduce the response rate. The responses in the survey are self-reported, and misunderstandings can potentially arise in the interpretation of the questions.

This study examines the self-reported experiences of 3 347 adolescents during the first lockdown, and generalisability is open to discussion. However, 3 347 is a large number of adolescents, and the school closure and reduced school health services were national measures.

Conclusion

In this survey, the adolescents reported that the first lockdown had both a positive and negative impact on their lives. They worried about being infected with COVID-19 but were more worried about infecting others. Few adolescents used a helpline or contacted a school nurse during this period. More girls than boys contacted a school nurse.

Few had been informed that they could contact the school nurse during the school closure. In such situations, it is important to provide accurate information on how to contact the school nurse and in which situations. Emphasis must be placed on ensuring a low-threshold service, even when the schools are closed.

References

1. Helsedirektoratet. Koronavirus – beslutninger og anbefalinger. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2020. Available at: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/veiledere/koronavirus (downloaded 30.04.2021).

2. Von Soest T, Bakken A, Pedersen W, Sletten MA. Livstilfredshet blant ungdom før og under covid-19-pandemien. Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening. 16.06.2020. DOI: 10.4045/tidsskr.20.0437

3. Qvortrup A, Qvortrup L, Wistoft K, Christensen J. Nødundervisning under corona-krisen – et elev- og forældreperspektiv. Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag; 2020.

4. Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, Reynolds S, Shafran R, Brigden A, et al. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2020;59(11):1218–39. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

5. Lee J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 2020;4(6):421.

6. Bekkhus M, Soest TV, Fredriksen E. Psykisk helse hos ungdommer under covid-19. Om ensomhet, venner og sosiale medier. Tidsskrift for Norsk psykologforening. 2020;57(7):492–501.

7. Riiser K, Helseth S, Torbjørnsen A, Richardsen KR. Adolescents’ health literacy, health protective measures, and health-related quality of life during the Covid-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0238161.

8. Unicef. Uten filter: Hva mener ungdom om myndighetenes håndtering av koronaviruset og smitteverntiltakene? Oslo: Unicef Norge; 2020. Available at: https://www.unicef.no/sites/default/files/2020-12/Uten%20filter_Undom%20i%20Norge%20om%20koronatiltak_lavoppl%C3%B8st.pdf (downloaded 30.03.2021).

9. Potrebny T, Wiium N, Haugstvedt A, Sollesnes R, Wold B, Thuen F. Trends in the utilization of youth primary healthcare services and psychological distress. BMC Health Services Research. 2021;21(1):1–12.

10. Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonal faglig retningslinje for det helsefremmende og forebyggende arbeidet i helsestasjon, skolehelsetjeneste og helsestasjon for ungdom. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2017. Available at: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/helsestasjons-og-skolehelsetjenesten (downloaded 22.03.2021).

11. Gammelsrud TF, Kvarme LG, Misvær N. Hvem går til helsesøster? Tidsskrift for ungdomsforskning. 2017;17(1):54–77.

12. Granrud MD, Steffenak AKM, Theander K. Gender differences in symptoms of depression among adolescents in Eastern Norway: results from a cross-sectional study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2017;47:157–65.

13. Bakken A. Ungdata. Nasjonale resultater. Oslo: Velferdsforskningsinstituttet NOVA, Oslomet; 2019. Rapport 9/19. Available at: https://oda.oslomet.no/oda-xmlui/bitstream/handle/20.500.12199/2252/Ungdata-2019-Nettversjon.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y (downloaded 05.10.2021).

14. Barne-, ungdoms- og familiedirektoratet. Utsatte barn og unges tjenestetilbud under Covid19 pandemien. Oslo: Bufdir; 2020. Available at: https://bufdir.no/globalassets/global/nbbf/bufdir/utsatte_barn_og_unges_tjenestetilbud_under_covid19_pandemien_statusrapport_1-konvertert.pdf (downloaded 05.10.2021).

15. KoRus-Øst. Om oss. Ottestad: KoRus-Øst. Available at: https://www.rus-ost.no/om-oss (downloaded 08.08.2021).

16. Bakken A, Pedersen W, Von Soest T, Sletten MA. Oslo-ungdom i koronatiden. En studie av ungdom under covid-19-pandemien. Oslo: Velferdsforskningsinstituttet NOVA, Oslomet. Report 12/2020.

17. Ungdata. Finn Ungdata-tall for din kommune. Oslo: Velferdsforskningsinstituttet NOVA, Oslomet; 2021. Available at: https://www.ungdata.no/ (downloaded 04.08.2021).

18. Branquinho C, Kelly C, Arevalo LC, Santos A, Gaspar de Matos M. «Hey, we also have something to say»: a qualitative study of Portuguese adolescents’ and young people's experiences under COVID‐19. Journal of Community Psychology. 2020;48(8):2740–52.

19. Eriksen IM, Andersen PL. Ungdoms tilhørighet, trivsel og framtidsplaner i Distrikts-Norge. En flermetodisk analyse av betydningen av bosted, kjønn og sosioøkonomiske ressurser. Oslo: Velferdsforskningsinstituttet NOVA; 2021. Report 2/2021. Available at: https://oda.oslomet.no/oda-xmlui/bitstream/handle/20.500.12199/6519/NOVA-Rapport-2-2021.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (downloaded 05.10.2021).

20. Helseth S, Christophersen K-A, Lund T. Helserelatert livskvalitet hos ungdom. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research. 2007;27(1):15–21.

21. Cowie H, Myers CA. The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the mental health and well‐being of children and young people. Children & Society. 2021;35(1):62–74.

22. Daks JS, Peltz JS, Rogge RD. Psychological flexibility and inflexibility as sources of resiliency and risk during a pandemic: modeling the cascade of COVID-19 stress on family systems with a contextual behavioral science lens. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2020;18:16–27.

23. Oldehinkel AJ, Bouma EM. Sensitivity to the depressogenic effect of stress and HPA-axis reactivity in adolescence: a review of gender differences. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2011;35(8):1757–70.

24. Utdanningsdirektoratet. Veileder om smittevern for skoletrinn 1–7. Oslo: Utdanningsdirektoratet; 2021. Available at: https://www.udir.no/kvalitet-og-kompetanse/sikkerhet-og-beredskap/informasjon-om-koronaviruset/smittevernveileder/veileder-om-smittevern-for-skoletrinn-17/ (downloaded 05.10.2021).

25. Fonn M. Ber helsesykepleiere si nei til koronaarbeid pa sykehjem og legevakter. Sykepleien. 03.04.2020. Available at: https://sykepleien.no/2020/04/ber-helsesykepleiere-si-nei-til-koronaarbeid-pa-sykehjem-og-legevakter (downloaded 02.05.2021).

26. Fish JN, McInroy LB, Paceley MS, Williams ND, Henderson S, Levine DS, et al. «I'm kinda stuck at home with unsupportive parents right now»: LGBTQ youths' experiences with COVID-19 and the importance of online support. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2020;67(3):450–2.

27. Granrud MD, Anderzèn‐Carlsson A, Bisholt B, Steffenak AKM. Public Health Nurses’ perceptions of interprofessional collaboration related to adolescents’ mental health problems in secondary schools: a phenomenographic study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2019;28:2899–910.

28. Hafstad GS, Augusti E-M. Barn, ungdom og koronakrisen. En landsomfattende undersøkelse av vold, overgrep og psykisk helse blant ungdom i Norge våren 2020: delrapport 1 av 3. Oslo: Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter om vold og traumatisk stress; 2020. Report 2/2020.

29. Moen ØL, Hall-Lord ML. Adolescents' mental health, help seeking and service use and parents' perception of family functioning. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research. 2018;39(1):1–8.

30. Skundberg-Kletthagen H, Moen ØL. Mental health work in school health services and school nurses' involvement and attitudes, in a Norwegian context. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2017;26(23/24):5044–51.

31. Granrud MD, Bisholt B, Anderzèn-Carlsson A, Steffenak AKM. Overcoming barriers to reach for a helping hand: adolescent boys’ experience of visiting the public health nurse for mental health problems. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. 2020;25(1):649–60.

Comments